This past week I’ve been seeing a few anniversary takes about March 2020. It was indeed four years ago that the fan was first hit and the storm began. The COVID experience has definitely turned the corner from seeming simultaneously like yesterday and hundreds of years ago, to just feeling like a hundred years ago. People talk about something happening before or after COVID. We hear talk of what has changed since, for good or for bad, but for the most part the pandemic and our experience of that time is gone and forgotten, no longer a part of our daily lives. And thank God, who wants to talk about viruses and ICU bed counts and masks all the time. There is so much more to life when we’re able to freely live it.

That said, it was a massive event, one that did change our lives and should give us a lot to learn from, if we’re willing to learn. Seeing the United States about to decide whether to put the same maniac who led them to have a disastrous COVID response back into office reminds us that it is important we dust off our collective amnesia from time to time. Looking back on how we handled this past crisis can help us better manage the next horror on the horizon.

With that in mind I include below an excerpt from Gathering Clouds, the first chapter of A Healthy Future about a speech I gave to the Saskatchewan Association of Rural Municipalities. That would ordinarily be about as exciting as it sounds. But this was no ordinary day. You can read the excerpt below, but first, a quick note on a friend’s exciting new project and two updates on the response to A Healthy Future.

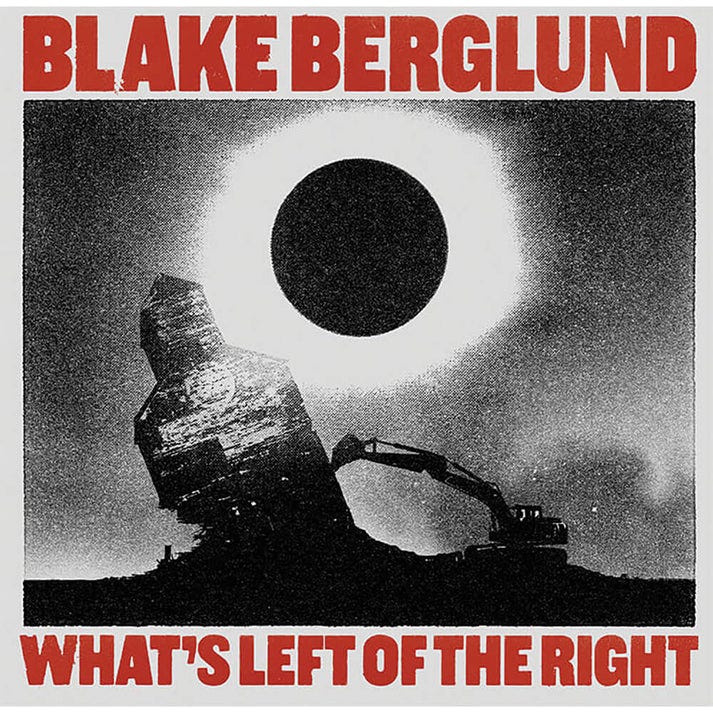

1) What’s Left of the Right

One of the positive COVID by-products was that, for all the disconnection, many people found time to reconnect with what they cared about the most. Musician Blake Berglund, his wife Melanie (aka Belle Plaine), and later their son Sam, were my downstairs neighbours the whole time I was in Regina. Blake was working on a concept album, a process that was deeply personal. He used a storage room connected to my apartment for some of his writing and plotting. As a result, I had a chance to witness him at work and have many a weird and wise discussion along the way. There’s no small talk with that guy, he gets right down to the big questions.

The same is true of his strange and beautiful double album: What’s Left of the Right. In his uniquely intense way, Blake explores farm life, faith, political corruption, masculinity, sobriety and leadership. It’s not an easy listen, his voice and lyrical style demand your attention and occasionally test your patience. Fortunately, he’s a great musician and enlisted some terrific supporting talent, which means you’ll be tapping your toes as you scratch your head and are sure to find yourself reflecting on more than just the melodies.

You can listen to the album here:

check out his Substack, The Straight & The Narrow:

and Belle Plaine’s Weather Report while you’re at it:

2) Pathogen On The Prairie

A Healthy Future was reviewed by John Baglow in this month’s Literary Review of Canada in an article titled Pathogen on the Prairies: Unmasking a Disastrous Response. Baglow begins by noting the continuity between this new book as a case study of the concepts in A Healthy Society.

“Meili’s latest book, A Healthy Future: Lessons from the Frontlines of a Crisis, should be read as a companion volume to A Healthy Society. Effectively a case study of the pandemic in Saskatchewan, it buttresses his previous argument by negative example. As Meili dissects the disastrous performance of Scott Moe and his Saskatchewan Party government, he tells a tragic tale of political failure: short-sightedness to the point of near-terminal myopia, crude knee-jerk responses, an anti-scientific outlook, and indecision and bad decision making.”

He then digs deeper into some of the key stories in the book and points out the importance of looking back at this tumultuous period and the political choices of those who failed to protect the people.

“even if he is looking through a partisan lens, Meili presents a series of facts, well-documented with footnotes, that speak for themselves. He has done us a service in meticulously chronicling a ghastly period.”

Baglow ends by picking up the larger lesson of the essential importance of addressing inequality in order to achieve better health for all.

“Our political culture, which favours mediocrity and business as usual, needs a serious health check. Until it is transformed for the better, inequality, in Meili’s words “the world’s biggest killer,” will remain at large, more dangerous than ever and claiming untold new victims.”

Read the full review here: Pathogen on the Prairie.

3) Saskatchewan Book Awards

And finally, the shortlist for the Saskatchewan Book Awards was released earlier this month. I was pleased to see A Healthy Future on the list for the Non-Fiction Award. The rest of the list is very impressive, so it would be a big surprise if AHF took home an award. Nonetheless, great to see it among good company and to be reminded of the great writing coming out of our province. See the shortlist here: Sask Book Awards.

Now on to that story of a politician saying no to shaking hands and kissing babies.

Our Separate Ways

I was invited to address the delegates at the annual convention of the Saskatchewan Association of Rural Municipalities (SARM). It’s no secret that the political fortunes of New Democrats in rural Saskatchewan have been disappointing in recent years, meaning this could be a tough crowd. In fact, it had been many years since a leader of the Opposition had been invited to speak, and on an ordinary day, I might have been nervous about the reception.

On an ordinary day, I would have started off talking about my own rural roots, about growing up on the family farm in the Rural Municipality of Rodgers, near Courval, where my brother Jim still farms today. I might have spoken about working as a family doctor all over rural Saskatchewan and the frustration of how decisions made in the legislature, not in the emergency room, make the biggest difference in people’s health. I’d have talked about how we need to work to address upstream factors if we want to keep people healthy. I would have then described how our plans would improve life in rural Saskatchewan compared with those of our opponents. You know, a standard political speech. Ordinary.

But this was no ordinary day. It was something completely new. This was March 12, 2020, the day it hit home that all of our lives had changed. We didn’t yet know how much, or for how long. We still don’t, I suppose. But that day in March we knew it had hit for real.

This was no ordinary day. It was something completely new.

The day before, the World Health Organization had declared COVID-19 a pandemic. A pandemic is “an epidemic occurring world- wide, or over a very wide area, crossing international boundaries and usually affecting a large number of people.” That classification made it clear: the new coronavirus would not be confined to one part of the world. It would spread everywhere.

The first confirmed case of COVID-19 in Saskatchewan was announced that day, found in a resident in their sixties who had just returned from Egypt. The first Canadian had died from the virus a few days earlier. Then US president Donald Trump, after initially dismissing the virus, had banned air travel from Europe. The upcoming Juno awards in Saskatoon were cancelled. The NBA season was suspended. Tim Hortons had cancelled Roll Up the Rim. It was a very big deal.

I told the audience that it was not a time to panic, not a time to buy a lifetime’s supply of toilet paper, but that it was time to act. And I described an idea, novel on that day, that we’d all get used to hearing: it was time to flatten the curve.

There are two possible distribution curves for infections in an outbreak: either one that spikes, meaning the virus is reaching those it will infect quickly, or one that is long and flat, meaning it’s moving more slowly through the population. With all the cases at once, the high spike curve, you get higher mortality, more health care workers are sick, health care services are overwhelmed – it’s a disaster.

Tim Hortons had cancelled Roll Up the Rim. It was a very big deal.

When the cases are spread out over time – the flat curve – more health care resources are available, there are potentially fewer cases overall, and there is lower mortality for those who do get sick. We may even be lucky enough to get into the vaccination and dedicated treatment window, as scientists everywhere, including at the VIDO-InterVac vaccine lab at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon, were already hard at work seeking cures and vaccines.

Key to that goal was another concept that was brand new to our vocabulary then but now seems so obvious: social distancing. We would later talk more of physical distancing, as we tried to emphasize avoiding the contact that could lead to infection but still reaching out in other ways to avoid loneliness and separation. When it came to distancing, Saskatchewan had some natural advantages. My favourite COVID T-shirt was one that read “Saskatchewan, physical distancing since 1905.” On my family’s farm, the next neighbour is a couple of miles away. Even in our largest cities, we don’t have the density of the world’s metropolises. While the number of people living in unstable housing has risen in recent years, most people in the province live in safe, clean housing. These factors protect us, but only if we’re careful, only if we do everything we can to reduce community transmission and make the extra efforts to keep the virus out of congregate living settings like homeless shelters, long-term care homes, and prisons.

In my speech to SARM, I called on the government to invite municipal leaders like the delegates present and their urban counterparts, First Nations and Métis leaders, leaders in K–12 and post-secondary education, in health, labour, and business to form an all-party, all-hands-on-deck table to start our response to COVID off right. Of all the calls to government that went ignored and unanswered during that period, this was the biggest missed opportunity. It was the moment we went into silos and guaranteed the political polarization of the pandemic response.

Thinking back to that day in front of SARM, with a crowd of hundreds of people from every corner of our province, it’s wild to imagine how we went overnight from gatherings of that size to many months apart. Despite the challenging message, people were ready to hear it. At that moment, while we were sending everyone to their separate corners, there was a heightened sense that we were all in this together. That we were about to face something massive and that it was going to take all of us. That in the face of such a challenge, there was a chance to look beyond whatever we thought divided us toward a common goal of getting through this with as many of us alive and well as possible. This has been challenged since, as missed opportunities and misinformation have reinforced and even worsened pre-existing polarization. Still, thinking back to that moment, to that supposedly tough crowd listening intently and ready to do what was necessary to keep themselves and their neighbours safe, reminds me that there is common ground and common purpose in most of us if we are willing to seek it out.

The separation of the months to follow made that harder, as we didn’t find ourselves in rooms full of new faces. We didn’t shake hands with strangers. We didn’t get to do the classic Saskatchewan social dance of finding out whom you know in common, how few degrees of separation there are between each of us. We now have work to do to make those connections again, and hopefully an even greater appetite to make them.

On that day, however, I urged everyone to skip the handshake. I joked that as a politician that was an extra burden: working the room is half the job description. It was indeed strange to, for the first time, refuse an outstretched hand. We all want to show each other respect and attention with a friendly, hearty handshake. But as one of the reeves reached out by reflex, I slid my hand in my pocket, said an awkward thanks for having me, and headed back to the legislature.

Always enjoy your blog posts. They are always interesting. Wondering if you've heard the latest on the SARM. Apparently they have put out a statement saying COs is not greenhouse gas - or something stupid like that. Gary and I find it increasingly frustrating living in a province of climate deniers and with a government that isn't the least bit interested in actually governing. I don't think we've had a more corrupt government in this province ever! And rural Saskatchewan continues to support these fools.