Later this afternoon I’m meeting Life of Pi author Yann Martel at a coffee shop in Saskatoon in preparation for tomorrow’s launch of A Healthy Future. We met up at the same coffee shop a few years back as part of a series of interviews I did for Upstream.

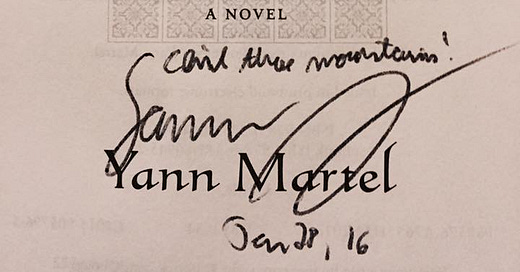

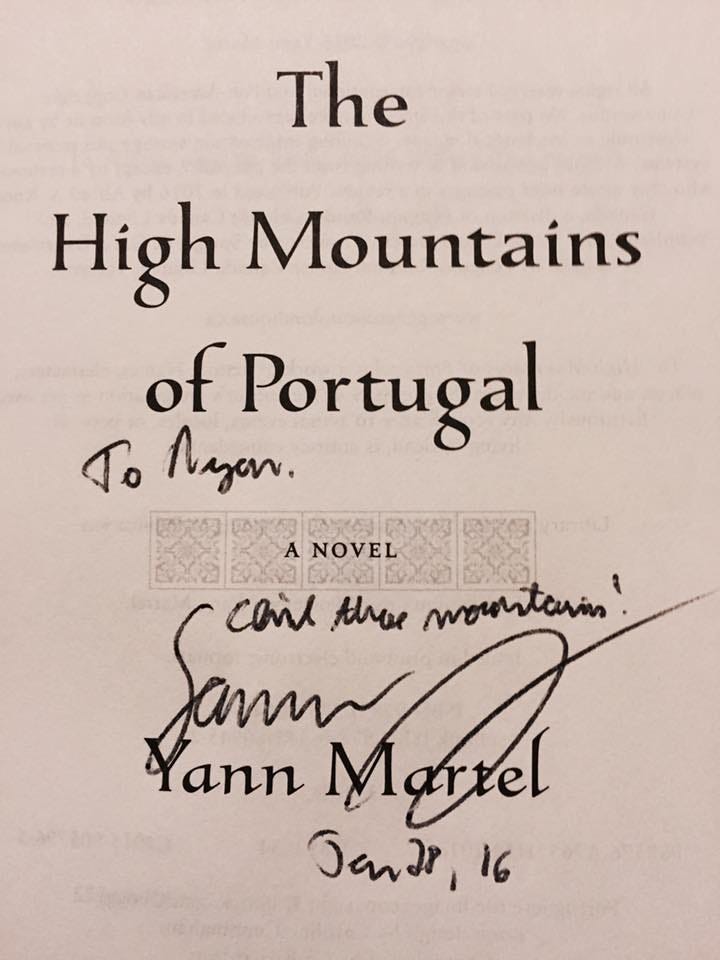

It was 2016, the federal government had just changed from the Harper Conservatives to the Trudeau Liberals and Yann was just about to release his strange and compelling novel, The High Mountains of Portugal. We talked about stories, inequality, faith and reason. Revisiting this conversation reminds me how thoughtful and eloquent Yann is and makes me look forward to tomorrow’s event even more.

Choosing the Better Story -

Yann Martel – The Upstream Interview - February 2016

Ryan Meili: You have a new book, the High Mountains of Portugal. Can you tell me more about that story.

Yann Martel: The High Mountains of Portugal is a novel in three parts. They're quite discrete, nearly standalone. One is set in 1904 - the story of a man who discovers a very old diary - it's 300 years old written in São Tomé - which is one of the Portuguese colonies of Africa - Africa's second smallest country - and it was very important during the slave trade.

It was a holding station for slaves on their way to Brazil, and later on to the United States. It was usefully located for ships about to do the Great Passage, the middle passage. He discovers a diary written by a priest in the 1630s that hints at an object that the priest creates. And this man, who's a minor curator in a museum, is very intrigued by this and decides to try to find the object. And it happens to be located in a very remote area of Portugal. So he has to get there, doesn't have much time, so his uncle lends him an automobile, one of the first in Portugal. So the first part is a road trip between Lisbon and it's sort of a tragic comedy.

Reason, while being a powerful tool, is only a tool; it's a means to an aim. And you need to find what your aim is to effectively use that tool.

Part Two takes place thirty years later and it's the story of a pathologist who's at work in his hospital trying to catch up on work writing reports. It's late — close to eleven o'clock at night, and two women in a row knock on his door to talk to him. All of Part Two is a long accounting of two conversations between him and these two women.

Part Three is the story of a Canadian senator in the 1980s that, after the death of his wife, goes to Portugal. He retires there to deal with the death of his wife, and it's an accounting of his time there. So there are certain symbols that resonate, a certain storyline that echoes through all three. And once again it's a kind of literary exploration of religion.

I'm from a completely secular background. Nonetheless, I feel that sometimes we've thrown out the baby with the bathwater in terms of our 'cult of rationality'. Rationality has achieved so much in the last 300 years in terms of technology, science, medicine — that's the miracle of paying close attention to details and drawing the consequences. It’s radically changed our lives, but this cult of rationality has led to a certain sterility in our lives as well. Reason, while a powerful tool, is only a tool; it's a means to an aim. And you need to find what your aim is to effectively use that tool. An obvious example is a phone or a computer - it's a fantastic tool, a marvel of complexity - but you need to find a reason to use it.

Reason, while a powerful tool, is only a tool; it's a means to an aim.

This is same reason why I wrote Life of Pi. Until the age of 33 I had zero interest in religion — I thought religion was for people who were ill-educated, ignorant in some way. But while I happened to be in India for a trip, for the first time I looked at it in a less pejorative way and was intrigued by that phenomenon called faith.

Why is it that after 300 years of the triumph of science there are still people who have these odd beliefs? And it's not just religion that involves an act of faith, but also romance — why fall in love with one person rather than another? So that led me to sort of a literary interest in religion and The High Mountains of Portugal is in that sense a sort of sequel to Life of Pi. It’s a totally different novel, but it's an interest in the same phenomenon.

Talking about these stories that illustrate deeper concepts, when we talk about Upstream thinking and action we often talk about our founding myth, the allegory of babies in the river. It’s a sort of parable that we try to use to illustrate a different way of thinking about health, politics, policy and science.

In Life of Pi you wrote about choosing the better story. Why are stories so important to us in making sense of the world or trying to craft a better world?

What's nice about the Upstream story is that it's extraordinarily brief, but it's an encapsulation of great complexity. That little myth, that story, you hear it - you remember it - and you understand it right away. And that's very powerful. Whereas, explaining it in more statistical terms would be less interesting and less understandable.

Stories are important because they frame us. Everyone has a story. We have individual stories, family stories, birthing stories, provincial stories, national and international stories. The weaving of all these together forms our identity. If you don't have a story, you're nothing, and you're lost. There is nothing sadder than people who have no story, and who have nothing to tell of their lives.

Stories are important because they frame us.

They’re also tools for understanding. After all, a story is a fiction, a selection of factual truths and fiction, which is to say interpretation of those factual truths to make it a coherent tale. A story is a simplification to bring clarity. Your little story with the babies is exactly that, it simplifies to bring clarity, to bring an essential truth. We need those truths. If you have no notion of truth, then you're lost: morally lost, socially lost.

Stories are tools for understanding our lives, hence the importance of literature. Literature is a marvelous way of refreshing yourself, because you're reading about someone else for a while. When you read a book, you are someone else for a few hours, a few weeks. It gives you someone else's life experience. The only other way you can get that is meeting very wise people who can very precisely tell you about their lives. Books allow you to live someone else's life and get a little bit of their wisdom.

You wrote one non-fiction book: What is Stephen Harper Reading? Why is it important for people in positions of political power to read literature? Shouldn't they just be reading the briefing notes and scientific reports of the statistics of the day?

Well, it was always an odd thing I did with Harper. It's not necessarily cause-and-effect. If I force-fed Moby Dick to the Prime Minister, would he necessarily be a wiser person? No. After all there are deeply moral people who have never read a single book, and they can be wiser than a professor at the university who might be a complete idiot. Literature has the potential to transform someone, but that person has to be ready for that transformation. Some people are, already, by natural inclination, by their family upbringing, by luck already open and curious and able to grow. On the other hand there are people who, even if given the greatest literature in the world would read it in a way that wouldn't allow them to improve because they’ve already decided on certain issues.

A book is an extraordinary treasure. Some people can understand how to exploit that treasure, for some it's wasted, pearls before swine.

What would you like to see be achieved, in Canada, now that there's been a change in leadership?

One of the glaring things is wealth inequality. There's plenty of wealth to go around, it's just appallingly poorly shared. You have people like Warren Buffett and Mark Zuckerberg and Bill Gates that have gazillions of dollars. Then you have people who don't earn seventy dollars in six months. Even Saskatoon is an encapsulation of that. You have the people who live on Sask Crescent and the people on the other side of the river. They live within 2 miles of each other and yet their lives are so different.

One of the glaring things is wealth inequality. There's plenty of wealth to go around, it's just appallingly poorly shared.

During the election I was so grateful to hear talk of taxing the wealthy. I love hearing that. I'm one of the wealthy. I made so much money from Life of Pi; I'm happy to pay more taxes. Not that you want to have a culture of charity, of depending on others. You want to empower people, but you certainly have to have income redistribution. I would like to see greater egalitarianism in this country, a Saskatchewan value until fairly recently.

I hope you enjoyed this interview from the Upstream archives. I’ll be doing more interviews in the months ahead. In the comments below or by email, let me know what other Canadian thinkers you’d like to see interviewed in this space.

Maybe Tammy Robert.

I hear she's in a tough spot right now.

I believe that you're familiar with tough spots, Ryan, and how to negotiate them wisely and effectively.

She could use a little help from her friends right now.

Thanks.

Dear Dr. Meili,

I recommend that you do an interview with Dr Gordon Edwards