Danger in Care

COVID revealed so much of what is wrong in how we treat seniors. Have we learned those lessons or turned our heads and kept on doing things exactly the same?

When Corey Atkinson saw his dad’s number on his phone, he felt a sinking feeling in his stomach. He’d seen the news a few days earlier that there was an outbreak at Parkside Extendicare, the long-term care (LTC) home in Regina where his mother, Myrna, was living. He knew what COVID had done in care homes in Quebec and Ontario and understood immediately that his family was in for hard times.

Canada’s first wave was marked by deadly outbreaks among residents and staff in LTC homes. More than 5,000 Canadian seniors living in congregate settings lost their lives in 840 COVID-19 outbreaks in the spring of 2020. This accounted for over 80 percent of Canada’s COVID deaths at the time, a rate more than twice the OECD average. In that period, seventy-four times as many elderly adults died from COVID-19 in LTC than outside. In Ontario, the Canadian Armed Forces took over five homes with particularly bad outbreaks, eventually releasing a scathing report that identified numerous problems, including staff moving from room to room without changing PPE, rooming of COVID-positive patients with uninfected residents, and a consistent lack of adequate staffing.

Today’s post is an excerpt from Chapter 8 of A Healthy Future: Respecting Our Elders. This chapter looks at the events in Long-Term Care in Canada during the pandemic, what that revealed about the way we treat seniors in Canada, and some ideas on how we could better support people as they age.

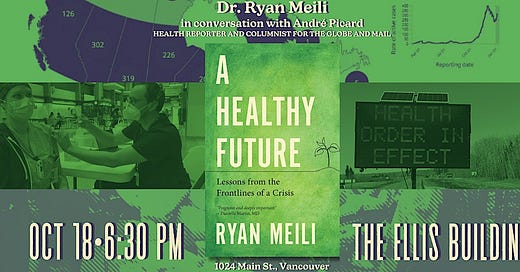

A good deal of inspiration for the chapter came from “Neglected No More: The Urgent Need To Improve the Lives of Canada’s Elders” by Globe and Maili health columnist, André Picard. André will be joining me for the Vancouver launch of A Healthy future tomorrow night at the Ellis Building on Main Street.

Event details and RSVP here: A Healthy Future Vancouver

Myrna Atkinson was born in Balcarres in 1954 and grew up on a farm near Broadview, not far from her mother’s home reserve of Cowessess First Nation. When she graduated from high school, she joined the military and met her husband, Steve, in basic training in Ontario. After a few postings, including several years in Moose Jaw, they settled in Regina. Steve continued in the military, but Myrna retired when their son Corey was born, working at Canadian Tire, Sears, and later with the provincial Information Services Corporation.

Her health began to deteriorate early on. She suffered from chronic renal failure and eventually needed a kidney transplant. She had severe back troubles, which limited her mobility to the point that there were several episodes where she couldn’t walk at all. After back surgery in 2014, she wasn’t recovering as well as expected and it was discovered she had chronic leukemia. After two or three years of exhausting struggle at home, where she needed daily therapy just to be able to walk, she ended up spending several weeks in the Regina Pasqua hospital. Myrna was stuck in the all-too-common limbo of being too unwell to go home, not sick enough to be admitted, but having nowhere else to go.

This is a chronic problem in our hospitals, where the lack of home care and LTC capacity leaves entire wards of patients “waiting for placement” for months on end. It costs $100 a day to support a long-term care eligible senior in their own home, $200 a day in a long-term care facility. In hospital, that cost rises to $750 a day. It’s an enormous added cost for an inferior experience, as even the most limited of care homes offers a more peaceful environment and more opportunities to socialize than a hospital room.

When Corey heard of the COVID outbreak, he knew Myrna was in real danger.

This warehousing of seniors in hospital wards also creates a chain reaction in the health care system. The “bed block” of occupied rooms leaves newly admitted patients in emergency rooms and hallways, making it impossible to receive all the patients who need care, leaving ambulances lined up in the parking lot and people at home unable to get emergency care. It becomes clear why patients, families, and staff are keen to find somewhere, anywhere else to go, often accepting something less than ideal just to get away from the hospital.

That’s how Myrna came to live at Parkside in late 2019, much to the disappointment of her family. When asked about this move, Corey said, “We weren’t crazy about it, to be honest.” They had hoped she could be in a place with her own room, but instead she was one of four residents to a room. “They were packed in like sardines,” he said. “It wasn’t safe.” These four-bed rooms had been flagged as out of step with current standards of care, including by then minister of health Dustin Duncan as far back as 2013.

Despite all of these health problems, Myrna made the best of her new home. At sixty-six, despite her serious health problems, she had energy for life. She looked forward to visits from her husband, son, and grand- children, even when COVID came and those visits had to be done through a fence in the yard. The loss of in-person visits was not only a source of isolation for residents, though that was of course a serious hardship. One of the ways of keeping staffing levels of LTC homes so low is by depending on family members to assist with the daily care of residents, helping with dressing, brushing teeth, and other time-consuming tasks. The loss of those extra hands highlighted the short-staffing and contributed to the oversights that would occur in the months ahead.

Corey, a broadcast journalist in Regina, was worried about his mother that fall. She told him she’d be wheeled out into the yard long before they arrived for their scheduled visits, and left waiting long after they’d gone. She’d been weaker and more tired since she’d caught a skin infection called scabies during an outbreak that fall. Parkside Extendicare was well known for its problems with infectious disease management. For example, from January to July 2020 the facility saw thirteen infectious outbreaks, including a gastrointestinal virus, scabies, and eleven respiratory viruses. When Corey heard of the COVID outbreak, he knew Myrna was in real danger. He thought of how fast the virus spread, of how she was immunocompromised from her leukemia treatment, and of that packed four-bed room.

The danger came. Corey got a call from his dad on November 21 – his parents’ forty-fifth wedding anniversary – that his mom had contracted COVID and was going to the hospital. A few days later she was in the ICU. Corey knew how serious the disease was and that in Myrna’s condition she couldn’t handle a long ICU stay. He started to prepare himself for the fact that this could be the end. He remembers waiting for his dad in the hospital parking lot, agonizingly close to where his mother lay dying but unable to go see her. He felt helpless, knowing that someone he loved and cared about was in such a desperate situation and that he couldn’t be there for her to see him, to know that he was there for her.

Myrna died on December 4 without Corey having a chance to even hold her hand and say goodbye. This left him feeling angry, feeling like something had been taken from him. He was angry that the government saw what had happened in Ontario and Quebec and hadn’t learned any- thing. That they’d seen so many infectious disease outbreaks in Parkside and hadn’t changed a thing to keep people safe. Angry that his mom was gone, her life cut short earlier than it needed to be, and that because of the pandemic the family could only hold a Zoom conference instead of a funeral.

Myrna was the second resident to lose her life to COVID-19 at Parkside in what would turn out to be a tragic winter. It started on November 11, 2020, when a care worker at the facility developed a cough and headache and felt dizzy. The next day they lost their sense of smell. They had followed the rules, wearing masks in public places and when working with residents. Staff were not required to mask during breaks, and residents did not wear masks inside or outside their rooms. Staff also frequently carpooled to work and did not mask in shared vehicles. Between November 9, when they would have been positive but asymptomatic, and getting a positive COVID-19 test on November 20, this staff member worked eleven shifts in the home. Two more staff members developed symptoms the following week.

On the morning of November 17, a resident was found slumped and unconscious in their wheelchair and was helped into bed. At the time their oxygen saturation (sats) was 94 percent. By evening, their breath had become “gurgly” and their sats were in the sixties. The resident was taken to hospital by ambulance, and, by two the next morning, had died from complications of COVID-19, the first Parkside resident to test positive and die from COVID.

“It was a war zone. We were losing people every day.”

The number of positive cases would rise to seventeen residents and seven staff a week later, and the facility started to isolate residents into positive and non-positive cohorts. The sheer number of cases and the lack of space made this a chaotic process, with staff and residents mov- ing between positive and non-positive areas, likely contributing to the spread of the virus. By December 6, there were ninety positive residents and forty-five positive staff, the Regina Fire Department had to be called in to provide staffing support, and twenty-five COVID-negative residents were moved to another care home in the city. Most of these residents would go on to test positive despite that move, though the outbreak did not spread into the Pioneer Village home that hosted them.

The Saskatchewan Health Authority then realized the situation was too severe for Extendicare to continue to handle it. They declared the outbreak an emergency, took over management, and put out a call to mobilize staff from across the health system. One staff member spoke anonymously to the CBC, saying that “it was a war zone.” “We were losing people every day,” he said. “It was unimaginable, the conditions inside. They were so short-staffed.” The death count continued to climb, with one or more deaths recorded nearly every day from the beginning of December into the New Year.

By the time the outbreak was declared over on January 21, 2021, 136 staff members and all but 4 of 198 residents had tested positive for the virus. Forty-two of those positive residents died, 39 from COVID-19 and another 3 reportedly from other causes, making it by far the deadliest outbreak in the province.