I walked down the back alley to the clinic where I work one frosty morning this fall. There are almost always dozens of people camped out or hanging around behind the clinic and Prairie Harm Reduction, the safe consumption site next door. That morning, three young men had started a fire in a tire rim. One was holding his arm over the fire, warming it up enough to find a vein.

People openly injecting in the alley and the yard outside St. Mary’s church. Illegal and diverted prescription drugs traded and sold right outside the pharmacy. Ambulance call after ambulance call. Overdoses responded to on the street, in emergency, in the clinic, and the ones that never get seen until it’s too late. These scenes are like a silent protest, revealing the injustice behind the desperate reality of the drug use, homelessness and toxic drug poisoning crisis of inner-city Saskatoon and so many places across Canada today.

Addiction is an illness. Dangerous drug use is directly related to traumatic childhood experiences, poverty, abuse and desperation, to the inequalities and inequities that plague our communities. Like any illness, we should treat the people suffering from addiction with compassion and care, working for recovery where we can and preventing the worst outcomes where recovery isn’t yet a possibility.

Those worst outcomes are increasing in frequency. The illness of addiction that years ago might have killed over long years of chronic alcoholism can now end a life in a moment. In Saskatchewan in 2023, there have already been 395 deaths associated with drug overdose. This puts the province on track to exceed the 2021 record of 408 deaths. Alberta has lost 1262 people to drug poisoning deaths in 2023, putting their population rate of drug poising at 41.1/100,000, a marked increase from previous years and approaching rates seen in B.C, Canada’s perennial capital of drug poisoning. These deaths are contributing to a nationwide drop in life expectancy unlike anything we’ve seen in decades, a trend I described in a previous post:

Efforts to reduce those deaths have become more creative in recent years, expanding from opioid agonist therapy (eg methadone or suboxone) to safe consumption sites to “safer-supply.” Safer-supply is the idea that people who are not yet ready to stop using be prescribed opioids that are a known quantity rather than taking the risk of scoring potentially dangerous drugs on the street. This practice was the subject of a recent report for BC’s Medical Officer of Health, Bonnie Henry. The report largely concluded that this is a necessary intervention, especially when today’s street drugs tainted with fentanyl, tranquilizers and benzodiazepines are killing multiple people every day. It also raised growing concerns that these programs lack the social supports to offer a path to longer-term sustainability and that they may lead to increased diversion, cheaper more available drugs, and new users.

A wicked, complex problem demands complex and creative solutions.

Deaths from toxic drugs are bad. Open drug use in our communities is bad. Spread of Hep C, HIV and all its opportunistic infections is bad. Increasing availability and getting more people addicted is bad. Filling jails with people who are sick is bad. Letting illegal drugs circulate wildly on our streets is bad. It’s the definition of a wicked problem, where simple answers have unintended consequences.

A wicked, complex problem demands complex and creative solutions. Unfortunately, in a time of hot takes and simple answers, the opioid crisis has become another “what side are you on” tribal badge. Thoughtful, reflective and compassionate practice are frequently lost in favor of a wedge issue that appeals to a political base.

Two simple statements from politicians illustrate this point. The first is from Tim McLeod, Saskatchewan’s Minister of Mental Health and Addictions, who recently defended his government’s continued choice to not fund consumption sites, saying: “If you’re using illicit and potentially lethal drugs, you’re not on the path to recovery.” He’s not entirely wrong. Using is not recovering. But his statement misses the point entirely.

If you’re dead, you’re not on the path to recovery. Preventing overdose is a worthy public goal in and of itself. Safe consumption sites and other services for people who are actively using save lives in the moment. They also serve as essential points of contact. As trust develops, as a window for change opens, a relationship can be a bridge to recovery.

If you’re dead, you’re not on the path to recovery.

McLeod’s recently announced Action Plan for Mental Health and Addictions has no mention of harm reduction, instead talking about “transitioning to a recovery-oriented system of care for addictions treatment.” It’s odd to think this is a transition. Wasn’t recovery always the goal? It’s hard not to see this language as a nod to similar, – and notably unsuccessful as the earlier overdose statistics show – shifts away from harm reduction in Alberta. As Saskatoon family physician Dr. Carla Holinaty told the CBC, "We can put a ton of money into recovery and detox and things like that, but we lose many people to overdose deaths before they even have a chance to enter into that program. They're not ready to go into those pathways yet. We still have an obligation to do our best to at the very least keep them alive."

The second simple statement comes from a (now-recovering) politician, me. During a 2017 debate in the race to become leader of the Saskatchewan NDP, I said (then live-tweeted by a campaign volunteer), that, “If you’re worried about a safe injection site in your neighbourhood, know that there are already a number of unsafe injection sites in your neighbourhood.”

That statement isn’t wrong. People are using all over: alone at home where they are more likely to die if they overdose, in alleys and parks and schoolyards where needles are left behind. But as a solution, this too is an oversimplification.

Supervised consumption sites are an essential element of harm reduction, helping to prevent overdose and the spread of HIV and Hep C. But they are a piece of the puzzle, not the whole picture. They can only be a bridge to recovery if there are recovery services available. Safe sites only reduce the unsafe if the larger community pattern is changed. Things don’t get better unless fewer people have nothing but drugs to help overcome past trauma or just make it through another night on the streets.

The growing number of overdoses and the scenes in back alleys and tent cities across Canada make it clear we aren’t yet getting it right. Complex, creative, systemic thinking is required to a complex, system-wide problem. Asking the question of whether we use decriminalization, diversion or safer supply, Drs. Jason Altenberg and Irfan Dhalla of the Toronto Opioid Overdose Action Network proposed an all-of-the-above approach. That all-of-the-above must go beyond strictly harm reduction actions to addressing the social determinants of addiction, including trauma-informed care, early childhood supports, safe and affordable housing, and ambitious efforts to reduce poverty in all its forms. It also includes law enforcement that gets the deadliest drugs off our streets without incarcerating those who are ill with addiction. And it needs to include linking harm reduction services to high quality, team-based approaches to long-term recovery.

“We need to be open to the idea that we might get it wrong.”

Some of these efforts will take years to have their effect. Some will need to be piloted and expanded. Some will have unintended negative consequences and need to be fixed or scrapped. I was struck by a quote from Dr. Nick Baldwin, an addiction medicine doctor from Kelowna. Interviewed about the recent BC safer-supply report, he called for transparency in the way governments would monitor the befits and harms of new approaches. “We need to be open to the idea that we might get it wrong,” he said, “There needs to be a lot of humility about it.” That doesn’t mean that we don’t try new paths. It means we reject simple answers that push people away. It means we embrace the complexity and do hard things together.

Three quick notes to go with today’s post.

Mahli and I are off at the beginning of December to Lesotho in Southern Africa to work with Partners in Health. Posts from our experiences there will make up the bulk of what you read from A Larger Scale for the next few months. You can see a powerful photo essay about the TB work in Lesotho here.

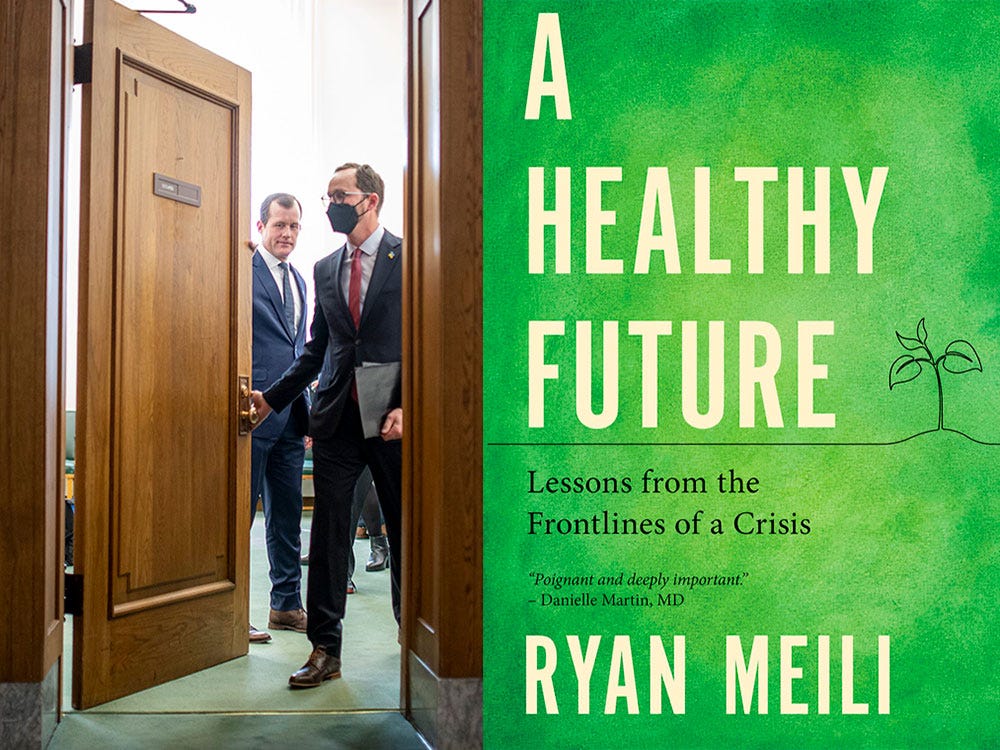

The last event of the Healthy Future book tour is 7PM, Thursday, November 23rd, at McNally Robinson in Saskatoon. Please join me and Child Psychiatrist Tamara Hinz for a discussion of the lessons we can learn from our experiences with COVID-19.

Crawford Killian at the Tyee has posted his review of A Healthy Future, check it out here: Clearing the Time Fog.

There is a need to discuss this at every kitchen table in Saskatchewan. No family is immune.

Agree with this being a complex issue, Ryan. I agree with increased community addiction treatment responses, but I'm not in favour of decriminalizing and harm reduction approaches (which tend to go hand in hand) based on what I intuit or info I've seen. Oregon is a canary in the coal mine for this type of approach and early data does not show success in the realm of hard stats (hard to quantify beyond overdose deaths). https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0167629623000759. The harm reduction approach also runs counter to what I and others intuit as parents, whereby an increased tolerance of destructive behaviours exhibited by our children might be better solved by waiting it out and letting natural consequences take their place. There are times and places for that parenting approach, but where collateral damage is taking place (ie two siblings fist fighting) it is easy to see that a more tolerant approach can have harmful consequences that could be prevented. Also in the realm of belief, no one will ever be able to count the overdoses prevented by police officers (or others) who confiscate drugs from addicts on the street vs letting them use them. Probably an area most can agree on is increasing enforcement on the supply side, difficult as that is.