This morning I drove to a side terminal at the Saskatoon airport with a Tim Hortons Take 12 and a dozen donuts. There I met with the team: TB nurse LeeAnne, Marvie, the MOA (medical office assistant), and Scarlett, the X-ray tech. With the help of the pilot and co-pilot, we load the portable X-ray machine into the 70s era King Air. We bundle up in our parkas in the plane, which always seems colder than the world outside. I put my trusty ear protectors on, read or write for a while, then fall asleep when the plane finally warms up. We often joke among the team that it’s the only job where you start the day by taking a nap together.

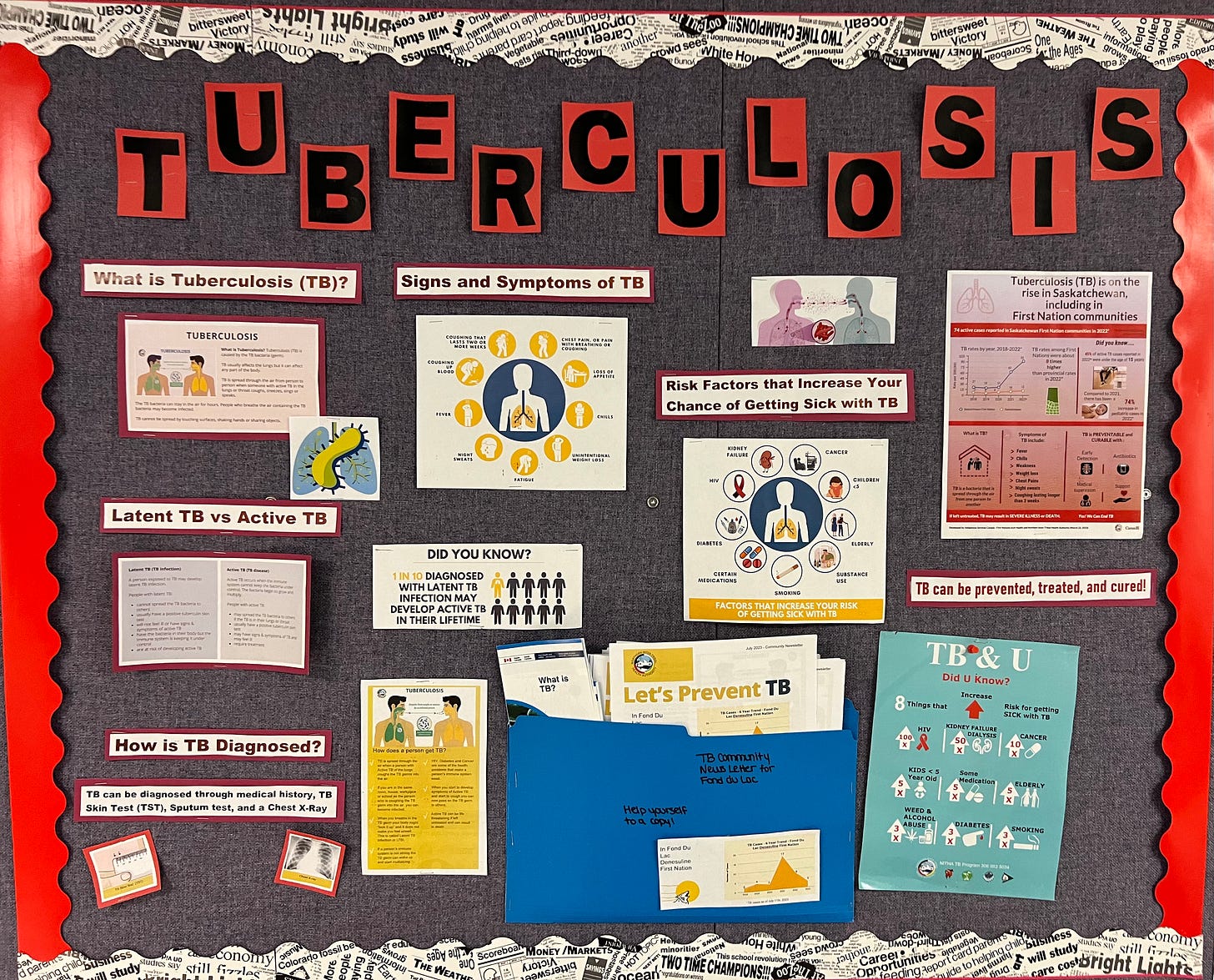

A little over a year ago, I joined the Tuberculosis Prevention and Control Saskatchewan program as one of the TB docs. This involves supporting TB care in a few specific communities and participating in call for new TB for the whole province. When I tell people that I’m working in TB, the most common response is, “we still have that here?” We think of this as a disease of long ago and far away. People assume that there is a vaccine (there is, it’s called BCG, but its effectiveness is limited, and it’s no longer used in most of Canada) and that it’s no longer an issue. Sadly, that’s not the case. Tuberculosis remains the deadliest infectious disease on the planet. Over ten million people worldwide had active TB in 2020 and 1.4 million died. It’s estimated that a third of the world’s population is or has been infected.

Here in Canada, most TB outbreaks are among newcomer populations and on-reserve First Nations communities. In Saskatchewan, TB has been largely eliminated from the general population since the onset of the antibiotic era in the 1960s when new treatments made the old sanitoria obsolete. For upstream reasons familiar to readers of A Larger Scale, the disease has stubbornly persisted on reserve, especially in the North. Rates had been falling during the early 2000s, but have more than doubled since 2019, with the COVID-19 pandemic playing a significant but not exclusive role in that rise.

As Dr. Nnamdi Ndubuka, medical health officer for the Northern Inter-Tribal Health Authority, told the Star Phoenix, “We are not supposed to see TB in Canada — not to speak of the outcomes, especially in children.” But that’s exactly what we are seeing. Outbreaks have been declared in multiple Northern communities. Perhaps most strikingly, about half of the new cases have been among children. There have been numerous hospitalizations, complications and even deaths.

“We are not supposed to see TB in Canada — not to speak of the outcomes, especially in children.” - Dr. Nnamdi Ndubuka

A few hundred miles, seven degrees of latitude higher and thirty degrees Celsius lower, the changing cabin pressure wakes us up and we marvel at beauty of the wilderness and the community below. The Athabasca region is a vast area just South of the border between Saskatchewan and the North West Territories. Lake Athabasca itself is a monster, practically a sea, and tens of thousands of snow-covered lakes and creeks dimple and crack frozen muskeg and shield. The local communities, on-and-off reserve, are connected by water in the summer, ice road and Skidoo trail in the winter. The Dene language remains strong, spoken by most of the people in the region, and traditional caribou hunting remains a major part of culture and sustenance.

Clinic staff meet us at the airstrip in a pickup, we lug the X-ray machine parts into the back and head over to the clinic for the day. Once inside, Scarlett sets up the machine, Marvie posts up in an office where she can check patients in and take their weights, and LeeAnne and I huddle with the local TB team. The local nurse and the TB workers are on the ground, connected to the community in ways we can’t be. We hear about their concerns and go through the list to see who’s coming today, who’s flown out of town, who’s been hard to reach. They tell us who they’re worried about and we decide whether to add home visits to our plans to try to catch up with someone who’s struggling more or has been hard to bring in.

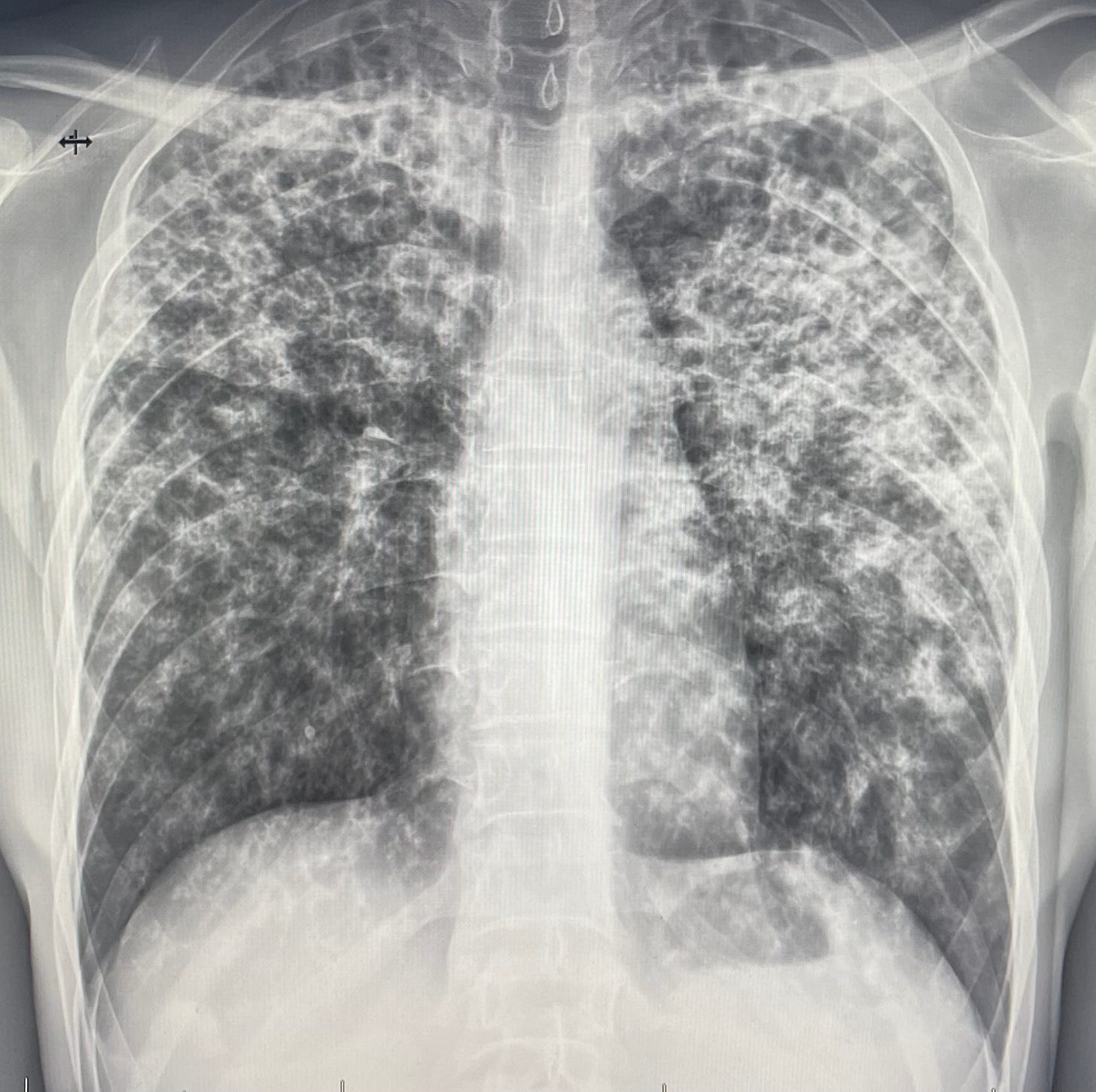

For the rest of the day, LeeAnne and I set up in a clinic room and see as many people as we can. Some are just there for active treatment. This means they have been infected with TB and it has made them sick. The vast majority of these have pulmonary TB (meaning the infection is in their lungs), though TB is a sneaky bug and can show up essentially anywhere: the brain, bones, eyes, skin, you name it. Those with active TB receive treatment for 6 months (longer for certain types), with TB workers coming to their homes for direct-observed therapy (DOT) to make sure they get all the doses needed for a cure.

Most of the patients we see are there for surveillance and prevention. Along with showing up anywhere, TB is good at hiding. Most people who are exposed to TB don’t get sick; their bodies are able to make the bug go dormant. We call this latent or sleeping TB, and most people have no idea they have it unless they’ve been identified in a contact tracing or have a positive tuberculin skin test known as a TST or a Mantoux. For example, I had a positive TST and some minor x-ray changes after spending the summer in India during med school but have never had any symptoms. These patients aren’t sick and can’t spread the illness, but sleeping TB can wake up again, making you sick months or even decades down the road.

The biggest risk for re-activation is in the first two years after exposure. Patients who have been identified as contacts and have a positive skin test are seen every six months for two years for a chest x-ray and symptom check. This way we can catch TB early if it does wake up and start treatment before people get too sick. Other patients choose the option of prophylactic treatment. A shorter course of the same meds we use to treat active TB can kill the sleeping TB as well, making it far less likely for reactivation to happen.

As you can see, there’s a lot to explain for the patients coming in and it takes humour and patience to make a connection. Often people’s eyes glaze over as we go through the differences between active and latent and the different medication regimens. One of the most helpful tools is the x-ray. Because we aren’t able to access the IT systems they have down South, we improvise. The tech takes a picture of the x-ray with her phone and texts it to me. I then review it for signs of TB and show it to the patient. Everyone, even the too-cool teenagers like to see their insides. I zoom in on the image and say “here’s your spine, here is your heart, here’s your lungs and what we’re looking for as signs of TB.” And for the five to ten-year-old crowd, or the rare adult who doesn’t appear to have lost their sense of silliness, I point at the bubble in the stomach and say “and that right there? That’s a fart.” The reference to breaking wind tends to break the ice and make patients feel sufficiently at ease.

Delivering TB care in remote communities is challenging. Poverty and crowded housing contribute to the spread of the infection and make it harder to get people their treatment. Stigma around the disease, much of it related to a history where people were taken away from the community to spend years in the sanatorium or to not return at all, leads to reluctance of community members and leaders to speak openly. Add to this the simple realities of communities being reachable only by airplane or ice road and the obstacles are obvious.

That said, we see incredible efforts by the TB team, with the TB workers and nursing staff playing an outsized role. They know the family trees and shifting relationships, they use Facebook and word of mouth to find their folks and make sure meds are delivered and ingested and contacts are screened and connected to care. In the last year, I’ve watched a community go from no cases to outbreak to calm and quiet again, witnessing how teamwork and leadership can get this bug under control and giving me hope that, as sneaky as TB, we can be sneakier. Canada has committed to eliminating endemic TB in our country and contributing to elimination efforts around the world. There's a great deal of work needed to make those commitments a reality, but it’s the right focus.

After seeing dozens of patients for x-rays and assessments, we say goodbye to the local TB team and jump back in the pickup. We catch our breath, visible as it is in the frozen King Air, after a hectic clinic day. These days feel good, we see people face to face and offer real help, effective treatment for active TB for some and important prevention. As always, however, there’s a frustration that we’re still dealing with outbreaks of this ancient disease. As satisfying as it is to offer care up close, it’s time for a larger effort to make TB truly long ago and far away.

I’ll be continuing to address other topics, of course, but you can expect a fair amount of TB talk from me in the next while. This is because I find it a fascinating and infuriating disease, but also because I’ll be seeing a lot of it. Mahli, Abe, Gus and I leave this week for Maseru, Lesotho to work with Partners in Health for the next six months. Lesotho has the highest rates of TB in the world and we’ll be working in Batšobelo Hospital, a dedicated centre for multi-drug resistant TB. If you would like to learn more about the work there, check out this story on the Partners in Health site.

Ryan, I miss you as a political leader, but you have always been a leader and still are. Thank you for all your efforts to bring health care to so many in remote areas and other countries.

All the best to you and Mahli and the boys as you launch into this adventure in Lesotho. Looking forward to hearing more about your efforts to join in the campaign to eradicate TB worldwide.