Trust Issues (Part I)

With an exclusive excerpt from Dr. Jane Philpott’s new book: Health for All

Hello Larger Scale readers. You may have noticed a gap in posts the last couple of weeks. There are a couple of reasons for this. One was a family trip to Mozambique to visit old haunts and friends and remember the days of the U of S Making the Links program.

See more about MTL and a very young-looking Dr. Ryan in this video.

The other was the realization that small children, laptops and hard tile floors don’t mix and subsequent technical difficulties and run across the border to South Africa to re-equip.

As thanks to loyal readers still with us after a longer-than-expected break, I’ve taken the paywall off this wander through some of the more exciting elements of Lesotho history via the Moshoeshoe Walk.

Now on to today’s post.

Trust Issues

Notices like the one above are popping up all over North America. One of the world’s most contagious diseases, declared eliminated in Canada back in 1998, is making a comeback and this had public health departments scrambling. This rise in measles, and other vaccine-preventable illnesses, is one of the predicted outcomes of the COVID-19 anti-vax panic. The short-term political calculus of those who sought to profit from the chaos of COVID has led to long-term disintegration of trust in public health1. A 2023 UNICEF study found that the number of Americans who think childhood vaccines is important had dropped from over 90% to 79% since 2020. Considering that a community vaccination rate of 95% is required to reach herd immunity for measles, that’s an alarmingly risky trend.

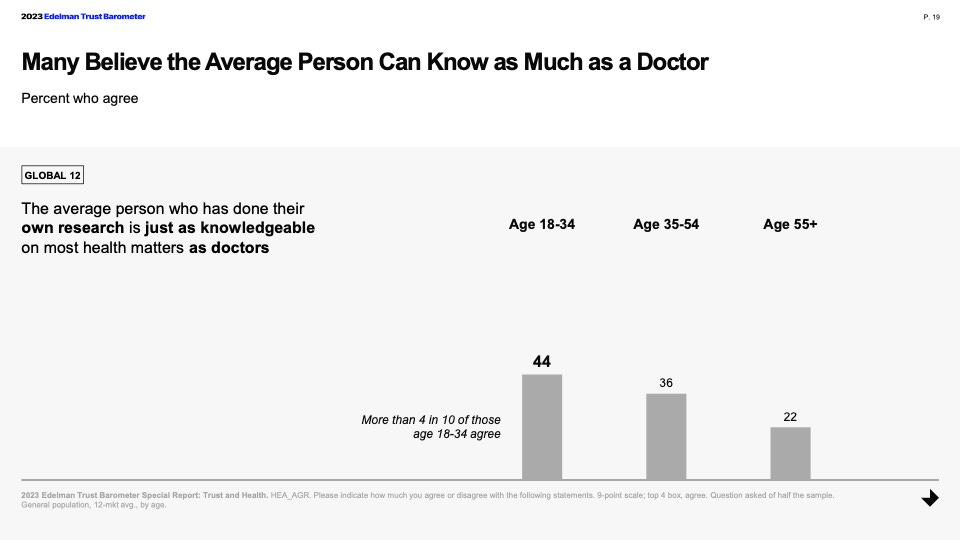

The World Economic Forum identifies “persistent false information (deliberate or otherwise) widely spread through media networks, shifting public opinion in a significant way towards distrust in facts and authority” as the biggest threat facing the world in the next two years. This includes misinformation impacting election outcomes and the growth of AI generated fake content, as well as the growth in mistrust of traditional sources of knowledge. That shift, where people put what they learn on social media and from friends and family on equal footing with information from content experts, creates opportunities for bad faith actors and peril for people in general.

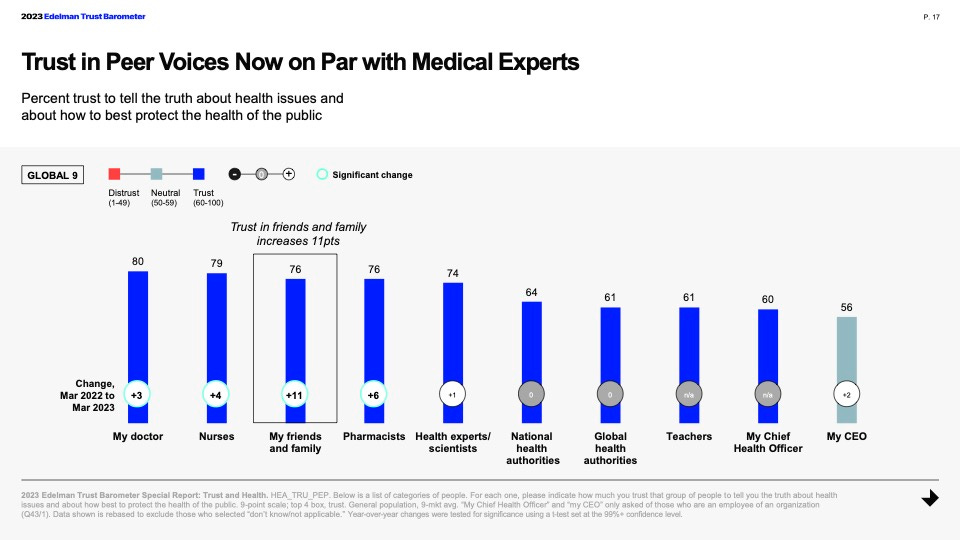

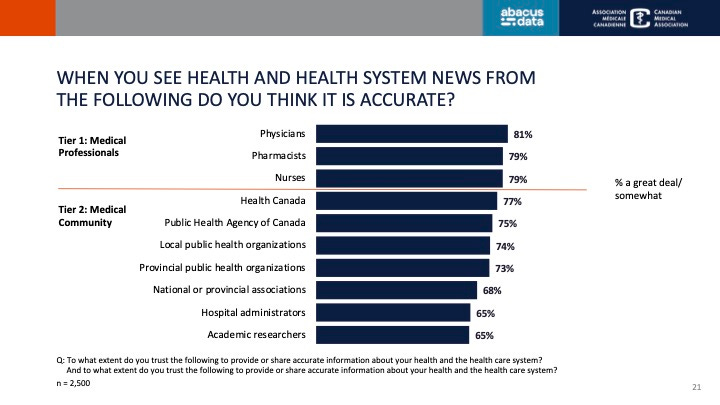

The above slides are from the Edelman Trust Barometer’s Trust and Health Report, a multi-country study showing shifts in public attitudes toward health and health information. A similar pattern was seen here in Canada with the Canadian Medical Association’s Health and Media Tracking Survey where, despite social media being recognized as a less credible source for health news, it is also increasingly where people, especially young people, are getting their information.

The better news in that report is that health care professionals are still seen as the best and most trusted source of reliable health information and advice.

Physicians and other health care providers remain at the top of the Trustometer, and can build on that public confidence with clear communication and regular interaction with patients and families that are making health decisions.

Establishing Care

CMA President and BC family doc Dr. Kathleen Ross makes a convincing argument on Healthy Debate that primary care providers are uniquely positioned to help Canadians separate fact from fiction. “Primary care physicians, in particular, have the chance to build long-term, one-to-one relationships with patients and their families. We provide opportunities for people to express their fears and make informed decisions relevant to their circumstances. We are the front door for health-care issues from birth to death and often serve as navigators for the rest of the health system.”

Primary care could be the key to turning back the tide of health misinformation, one conversation at a time. But that only works if people can access that care. Today, over 6 million Canadians don’t have access to a primary care physician. These shortages are worse in lower income communities and areas with lower levels of formal education where the risk of misinformation being accepted is higher. For primary care to serve the purpose of providing health guidance people can count on, they need to first be able to count on being seen when they’re sick.

Former federal Minister of Health, Dr. Jane Philpott, has written a new book, Health For All: A Doctor’s Prescription for a Healthier Canada. It’s a remarkably personal and profound book, full of valuable insights beyond health care,, as well as an important road map for how we get people the care they need. Central to this plan is the idea of a Canada Primary Care Act that would establish legal right to a primary care home. She bases the structure of such a program on the public school system, writing that, “Simply put, we must make it a reality that every person living in Canada has a primary care home, just as every Canadian child has access to a public school.”

Hear Dr. Philpott discuss this idea on CBC’s The Current.

A Canadian Health Care Dream2

Imagine it is 2035 and we are celebrating our collective success. After a decade of hard work, we can finally say that every Canadian has a primary care home. In each community, it is the front door to health care, the first location you call or visit unless you have a highly time-sensitive emergency. This is the place where the members of the care team know your name. They use it when they welcome your arrival with genuine warmth.

Your primary care home is staffed by a team that includes doctors, nurse practitioners (nps), nurses, and administrators, plus others according to the specific community needs. Some primary care homes have physiotherapists, occupational therapists, physician assistants, midwives, social workers, dieticians, pharmacists, and community paramedics. Where possible, the team is enhanced by the presence of health sciences students, as well as community volunteers. This is more than a collection of different health professionals and social service workers. They are more than the sum of their parts. They are trained to function as an integrated team in the delivery of care.

You have a long-term relationship not only with your family doctor but with that entire team of professionals. Your electronic medical record (emr) is collated in one place. You and your other care-team members can access that information according to the permissions you set. If you move to a new community, and you grant permission, the emr automatically, digitally, follows you.

Speaking of moves: If you do relocate, you are reassigned to a new primary care home based on geography, generally according to your place of residence. You do not need to beg for a family doctor or wait for years on a list of “unattached patients.” Unless it’s close by and you choose to return for care, you do not need to drive or fly back to your previous municipality to see the family doctor you had there. Your care is delivered close to home, ideally accessible within thirty minutes of where you live or work.

The doors of most primary care homes are open seven days a week, up to twelve hours a day. As the open front door—or the figurative first floor—of the health care system, these primary care homes offload pressure from emergency departments and enable hospitals to discharge their patients in a timelier way.

You can book appointments with your regular doctor or nurse practitioner for preventive care checkups or follow-up visits for chronic conditions. If you need to be seen on short notice, you can walk in for care. The triage team at the primary care home determines how quickly you need to be seen, and which clinician is right for you on that occasion. In some cases, care is offered virtually, as long as it is safe to do so. After your visit, you are encouraged to provide feedback by text message or on a website. This is used to improve the quality of your care experience and health outcomes, continuously and iteratively.

The primary care home is the coordinating centre for home care, including palliative care. When needed, someone from the team will see you at home or in the community, always ensuring the visit is linked to the primary care home and your records are updated in real time.

Where possible, your primary care home is a one-stop shop for other health-related services. This may include public health clinics or classes on topics such as nutrition, prenatal care, or mental wellness. Other specialist physicians are available to see you when they make regular visits to the local primary care home. Primary care homes also offer additional social services such as legal clinics, tax clinics, and mobility services. They are the heart of an integrated health system.

This may sound like a dream. This dream could be our reality.

I’m grateful to Dr. Philpott for sharing this excerpt and highly encourage you to find a copy of Health for All. Her personal and political journey and her inspiring and achievable vision for what Canadian health could be are worth your time. You can watch the two of us in conversation at Queen’s University where she is Dean of Medicine in the video below.

Public health had a role to play here as well, more on the communication shortcomings and strategies to learn from them in Part II of this series.

Excerpted from Health for All: A Doctor’s Prescription for a Healthier Canada by Jane Philpott, Chapter 1: A Canadian Health Care Dream. Copyright ©2024 Jane Philpott. Published by Signal/McClelland & Stewart, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the Publisher. All rights reserved.

Wading through the misinformation has always been part of my job as a public health nurse, but the marked increase in that, topped with active disinformation campaigns the last few years, it’s a now become a mammoth challenge. Some of the claims are just bizarre. As an individual health care worker, I keep having those important conversations one by one with clients and do my best on socials to share the most reliable information I can. And yeah we now unfortunately have “Measles Alert” signs hanging in our offices…