My first patient of the week was in a deep sleep on the exam bed when I walked into the room. The next patient was slumped over the desk asleep on her outstretched arms, her hood up over her head. The third patient I saw was in the same position. Why was everyone so tired?

Fall has arrived in Saskatchewan. The temperature drops to near or below zero at night. Sleeping on the street is getting less comfortable as summer fades. So people stay up later, sleep worse, and look for somewhere safe and warm when morning rolls around.

Homelessness in our city has changed. It’s not a few hard old men sleeping rough under bridges or in tents by the river. More young people, more women, more children have moved from the relative homelessness of overcrowding or couch-surfing to life on the street for long stretches at a time. That morning at clinic, Toby, the Director of the West Side Community Clinic, told us how on every block of his drive from downtown to the clinic there was at least one person asleep on the sidewalk.

The number of people without a place to stay has risen dramatically across Canada. A report this week showed that in just four years the homeless population of Quebec has doubled. Saskatchewan has seen similar spikes while, as Social Services critic Meara Conway pointed out this week, over half a billion dollars worth of housing sits empty. Winter is on the way and there’s no plan to get people shelter.

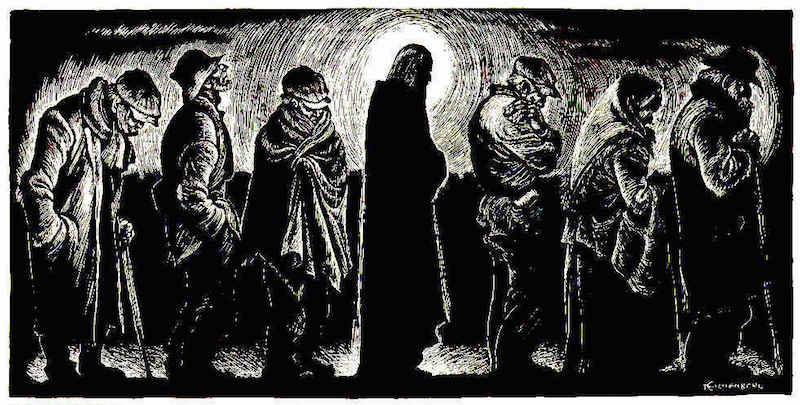

I wrote about homelessness in one of my first posts, No Trespassing, and should perhaps be covering other topics. But I can’t stop thinking about the people. The patients asleep in the exam room, the dozens of people in the back alley behind the clinic every day, the young woman who’s been living on the park bench across the street from our house. The root causes are complex: family dysfunction, mental ilness, intergenerational trauma, systemic racism, drugs that are cheaper and more dangerous than ever. We need to work upstream and keep people from winding up homeless, but that isn’t enough. How do we help the people drowning today, and what does the fact that they are in such dire straits say about us as a society?

A Preferential Option

I went to visit Father Les Paquin yesterday, or Padre Les as I always think of him. Padre Les is a diocesan priest from Saskatoon who spent several years serving the parish of União dos Palmares in Alagoas, one of the poorest states in Brazil. When I was in my early twenties, I spent a few weeks learning from him and his colleagues in União. I witnessed the humility with which they worked with the community and the bravery of standing alongside the landless and the oppressed.

After leaving União, Padre Les came back to Canada for a few years before returning to Ibateguara, a more remote community in Alagoas. While there, he came down with a mysterious illness that still plagues him today. Struck with severe chronic pain, limited mobility and constant illness, he now lives in a long-term care home in Saskatoon. His has become a ministry of suffering, of finding gratitude and grace despite his agony. Amid all that difficulty, he still lights up when he talks of the mission of serving the poor. “Whatsoever you do to the least of my brothers that you do unto me,” he explained to me, is the heart of his faith.

In the same vein, Paul Farmer, author of Pathologies of Power and co-founder of Partners in Health (PIH), famously said that, “The idea that some lives matter less is the root of all that is wrong in the world.” He co-founded PIH with a vision that high quality health care should be available to everyone, not just wealthy people in wealthy countries. Instead, he spoke of a “preferential option” for the poorest and most vulnerable; those who need care the most should get the best care, not scraps and neglect sold as sustainability. If you’re interested in learning more about Farmer – who passed away in 2022 leaving a tremendous humanitarian legacy – and the courageous work of PIH, I highly recommend the biography Mountains Beyond Mountains or the film Bending the Arc on Netflix.

When people are lying on the cold concrete with winter on its way, when they can only find comfort in a few stolen minutes of sleep in the doctor’s office, there is something more than just policy that has gone wrong.

That vision of all human lives being of value, of seeing the divine in everyone and seeking to serve those most in need, speaks to me deeply. I won’t pretend for a moment that I get it right, that I don’t far too often serve my own interests first, walk by someone without noticing their need, or lose sight of how important the patient in front of me is in the rush to get through the day. But I am inspired by and admire those that live these values and I try to find, in better moments and small efforts, a way to live that spirit in my work.

For those who follow A Larger Scale for commentary on politics and health, my apologies if this has strayed too far into the personal and philosophical. I would just say that what we see on the streets around us is, or in our emergency rooms, shelters and prisons, is a statement of our values as a society. Are we comfortable with the idea that some lives matter less, that some people are going to be cold and hungry while we’re warm and well-fed? When people are lying on the cold concrete with winter on its way, when they can only find comfort in a few stolen minutes of sleep in the doctor’s office, there is something more than just policy that has gone wrong.

Celebrating the Helpers

Later this year, our family will travel to the tiny mountain kingdom of Lesotho, an independent country located within the borders South Africa. Lesotho has the highest rate of tuberculosis in the world, the second highest rate of HIV. Mahli and I will work in the Botšabelo TB hospital in Maseru and assist with remote village clinics as part of PIH’s ongoing work in the country. Above all, like Padre Les in Brazil, we will listen and learn from the people there and help in whatever way we can. I’ll also be sharing regular stories from our experiences there with you.

Over the next few weeks, along with broader topics of health and politics, I will be writing more in this space about Tuberculosis Prevention and Control, the REACH refugee clinic and the WestSide Community Clinic. These are the places I work and witness the courage of patients in the face of challenges and the dedication of the health care workers who have chosen a life of service. I would also love to hear more from you, in the comments below or by email, about the Farmers and Fathers in your world. We all have much to say about what’s wrong with the world, let’s make sure to remember the people working hard to make things right.

A reminder that A Healthy Future: Lessons from the Frontlines of a Crisis is coming out very soon! I’d love to see you out at one of these upcoming book events.

Saskatoon: Sept. 20, 7PM, Le Relais (308 4th Avenue N), with Yann Martel, RSVP.

I’ll be on CBC Saskatchewan’s Blue Sky that day at noon to talk more about the book.

Toronto: Sept. 26th, 7PM, The Dais Institute (9th Floor, Atrium on the Bay, 20 Dundas St West), with Dr. Danielle Martin, RSVP

Ottawa: Sept. 27th, 7PM, Douglas Coldwell Layton Foundation (1404 Scott St.), with Dr. Danyaal Raza

Kingston: Sept 28th, 3PM, Robert Sutherland Hall, Queen's University, with Dr. Jane Philpott, RSVP

Regina: Sept 30, 1:30PM, Tuppenny Coffee & Books (1433 Hamilton Street), with Andrew Stevens, RSVP

Vancouver: October 18th, 7PM, The Library at the Ellis (1024 Main St.), with André Picard

I like the personal and philosophical when it helps to illustrate your concern. I have an image now of a homeless person sleeping on an examination table. Good work.

What you have described in this post is the definition of Christianity, the embodiment of Christianity. Thank you for reminding us all about what is important in life. We ARE our brothers'/sisters' keepers.