Love and Consolation

A World TB Day photo-essay on the the team fighting MDR-TB in Lesotho

Today is World TB Day, commemorating Robert Koch’s discovery of the mycobacterium that causes the disease, a discovery that led to the development of diagnosis, treatment and a cure for TB. It’s a day to remind people that TB, despite being curable, is still the world’s deadliest infectious disease.

This post features the work of Josh Berson, a Vancouver photographer who uses his camera as a tool for social change. He travelled to Lesotho to see and show the work of PIH alongside patients and turned his lens on our patients and the team working with them to fight MDR-TB.1

Mahli and I presented these stories to the University of Saskatchewan’s Global Health: Lessons from Abroad Conference earlier this month. You can see the full video of that presentation, including Q&A, here:

Note: the photos make this post long for email, click here to see it in your browser for the whole story.

Love and Consolation: Mots’elisi’s Story

‘Mme ‘Malerato (lerato means love, ‘Malerato, mother of love) has made the trek from her house to visit Mots’elisi twice a day for the last six months. It’s only about a twenty-minute walk, but the dirt paths through the hills of Qacha’s Nek, Lesotho, can turn treacherous in the rain and snow.

Still, ‘Mme has never missed a day, she takes her job too seriously. She is Mots’elisi’s “treatment supporter”, hired by PIH to accompany her from the beginning of her care for Multidrug-resistant Tuberculosis (MDR-TB) to the end.

Mots’elisi (whose name means consolation) is twenty-five. She usually lives with her mom, her brother and her two-year-old son Hlalele, but she’s been staying on her own in a small house nearby since was diagnosed with MDR-TB last July. This new illness came about six months after she’d been diagnosed with HIV and started anti-retroviral therapy. “I noticed I was losing weight,” she told me, “And then I started to cough up blood.” She figured it was TB because these were the same symptoms she’d had ten years earlier when she’d been treated for drug-sensitive TB.

At the hospital, she provided a sputum sample. A GeneXpert PCR test was positive for Mycobacterium Tuberculosis, the bacteria that causes TB disease. This time the bug was resistant to Rifampin, one of the key drugs for treating tuberculosis. This meant her TB couldn’t be treated with the regular drugs and she would need to be enrolled in the MDR-TB program. She is not alone in this diagnosis. TB affects a quarter of the world’s population, MDR-TB makes up 3.5% of new cases and 18% of cases among people previously treated for TB. Lesotho has the highest per capita rate of TB in the world2, major challenges in diagnosis and treatment, and a high burden of MDR-TB.

The care of MDR-TB is challenging, and for patients like Mots’elisi it takes a team.

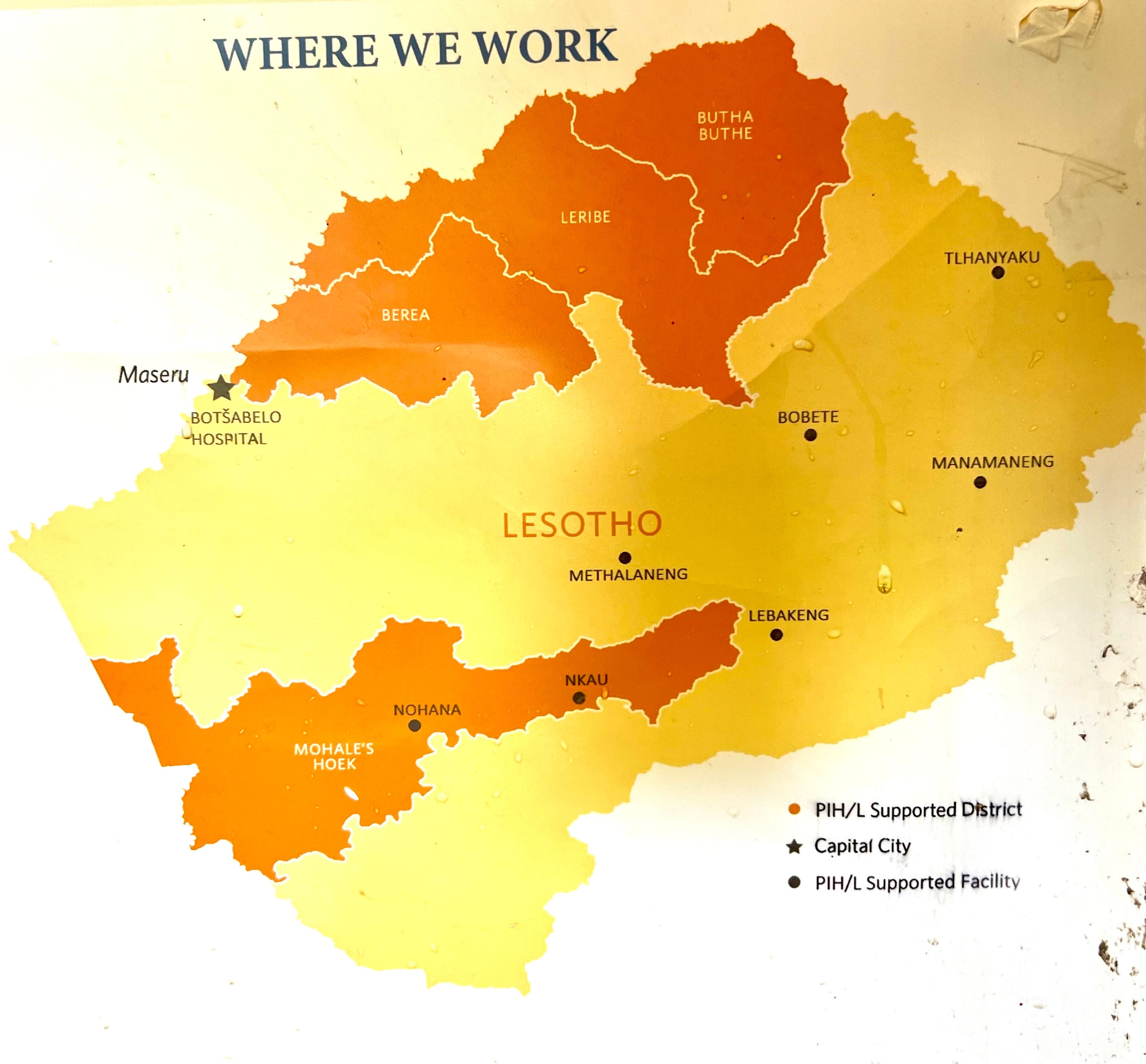

The team we’re working in Lesotho is supported by Boston-based global health NGO, Partners In Health (PIH), three main activities: rural initiative (RI), establishing primary care in remote communities, Health Systems Strengthening: supporting the Ministry in developing the 5S S’s Staff, Stuff, space, systems, social support, and MDR-TB, delivering care in Lesotho3 in partnership with the Ministry of Health. The map above is from the wall of one of PIH’s rural clinics, showing the remote RI sites.

Most of the work is on the ground, but some of it very high level. Lesotho the highest country in the world, tiny, but geographically challenging. Many of the communities we serve accessible only by rocky mountain trails, and occasionally by helicopter or small plane. Here Mahli joins PIH Lesotho Executive Director Dr. Melino Ndayizigiye, Clinical Director Dr. Afom Andom, and US Emergency Physician Dr.Chanel Fischetti for a tour of rural sites.

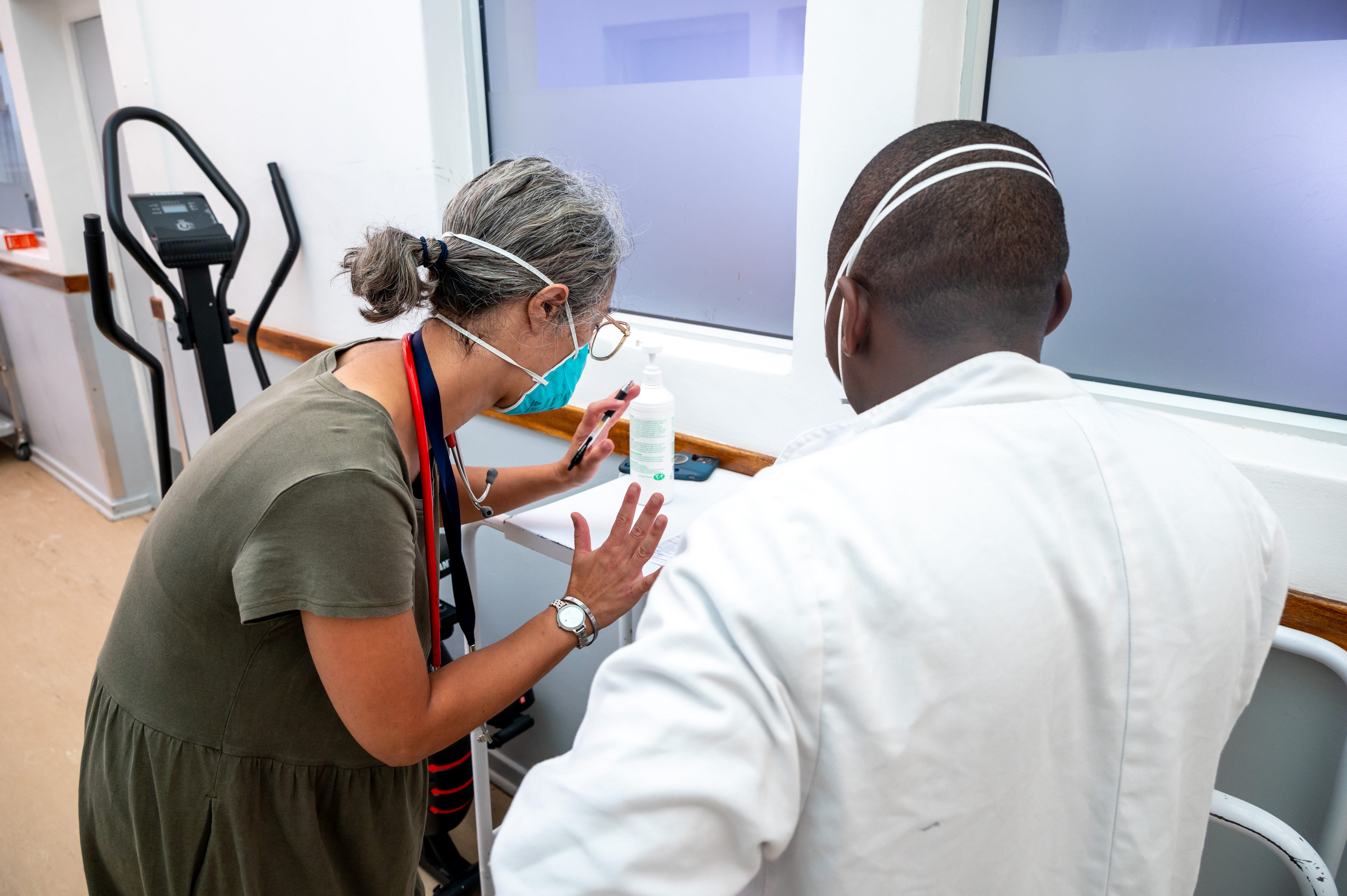

Dr. Melino demonstrates the use of POCUS (point-of-care ultrasound) at the partner Senkatana oncology centre next to the MDR-TB hospital.

The first step to MDR-TB treatment is diagnosis. Ntate Rethabile and his team at the Botšabelo hospital lab use GeneXpert PCR to diagnose TB and which drugs its resistant to, as well as following many other key lab findings, including the CD4 counts and viral loads of the approximately three quarters of MDR-TB patients that are also living with HIV.

Some of the patients are sick enough at diagnosis or later in treatment to be admitted to the Botšabelo MDR-TB hospital where they are cared for by a team of nurses, ward attendants, x-ray technicians, mental health counsellors, cleaners, and administrative and logistical leaders as well as the medical team of general practitioners, internists, a critical care specialist, a pediatrician, an infectious disease specialist, and a radiologist.

Most of the patients are adults, like Mme Selloane, here being examined by Dr Ninza, a critical care specialist from Zambia. Selloane has been in and out of hospital due to complications of her care, with added challenges as she lives two hours by horse from the highway. Fortunately, after months of treatment and observation, she’s now back home and doing well.

Though we do provide our pediatrician (and her assistant) with the occasional child, like my friend Tlotla who came with us from one of the mountain communities to be worked up and have his treatment started in hospital.

The sickest of the patients are seen in the ICU, where the team provides high quality care, consistent with the philosophy of PIH that everyone deserves to benefit from the best of scientific advances. PIH promotes the notion of a “preferential option for the poor” in its medical services4, believing that people shouldn’t be denied good care because they live in poverty, that those most in need deserve the most help.

Ntate Thulo and the pharmacy team prepare the medications, including the highly specialized MDR-TB drugs, for the inpatients and for the bulk of the MDR patients who are seen in the community.

As part of the MDR-TB program, also operate rotating community clinics in nine of the country’s ten districts. Here Mme Mpho, a member of the community nursing team, prepares the files, making sure everyone’s labs and meds are up-to-date.

In the warehouse, Ntate Malefetsane, prepares the food packages – maize flour, sorghum flour, beans, peas, sugar and oil – each patient receives throughout their care. Malnutrition is a major risk factor for catching TB and in success or failure of treatment.

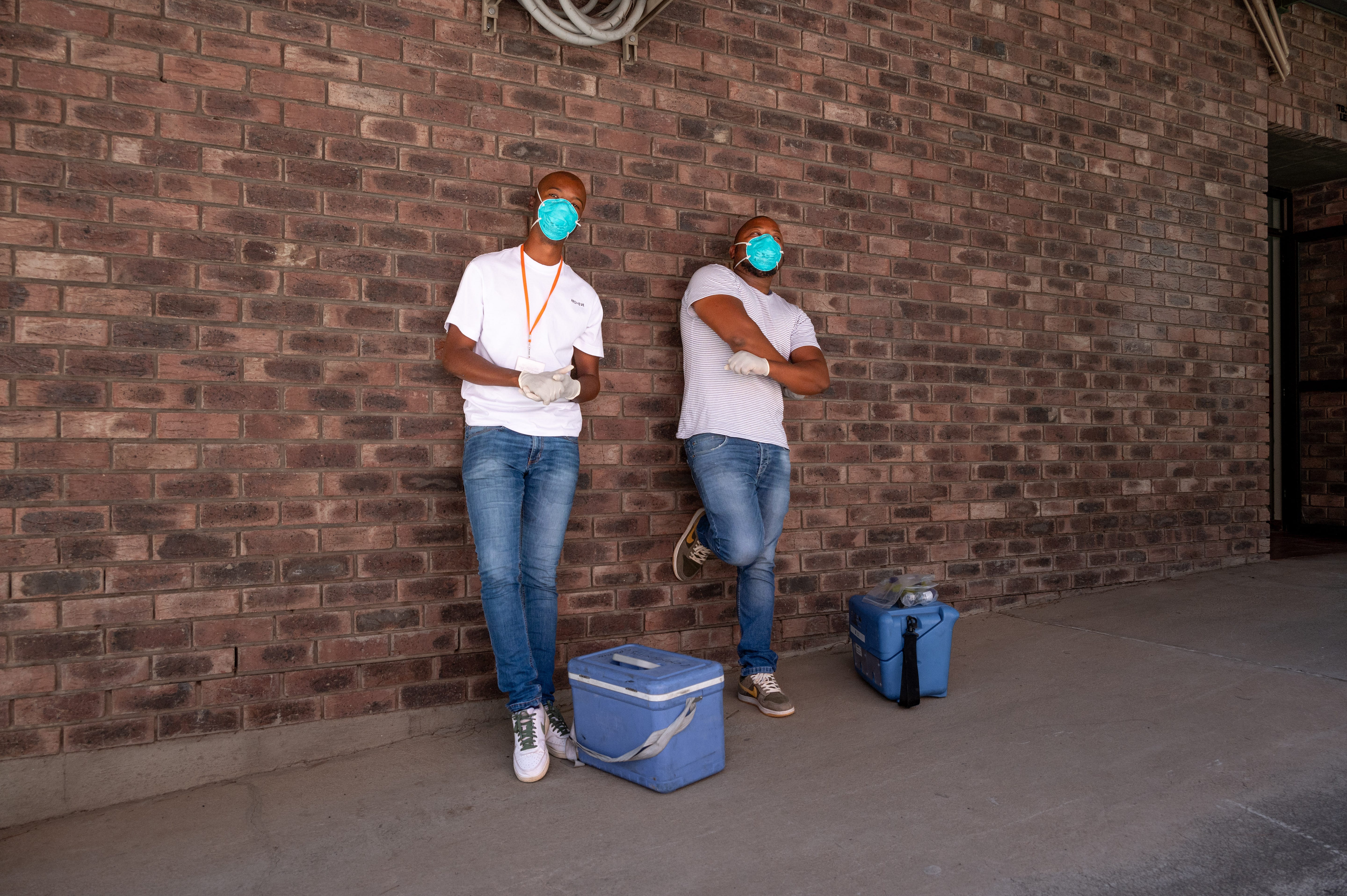

Loaded up and ready to go, the team is ready to head out to the district health centres.

The roads are long, switchbacked and frequently treacherous in the high mountains.

But we’re in good hands with drivers like Ntate Matlosa who has a keen eye for potholes and crossing sheep and cows.

Here we see Community Nurses Lebitsa and Ntsapi looking badass enough to tackle any mycobacterium.

Each outreach team consists of a doc, driver and two community nurses. When we get to clinic, we unload the files, medications and food packages, then start seeing patients.

This is where we meet Mots’elisi, at Machabeng Hospital in Qacha’s Nek. After listening to her lungs and heart, reviewing her chest x-ray and renewing her prescriptions…

we went to visit her in her home. One of the key beliefs of PIH is the importance of accompaniment, of walking alongside our patients. wanted to know more about her experience with MDR-TB and particularly with the PIH team.

And it’s a big team. She would only know the people she was directly in contact with, like our group that had come out for clinic. The people you see in today’s presentation represent a much larger operation. There are over 450 staff and over 125 treatment supporters working for PIH in Lesotho.

Undergoing a treatment that involves taking medications daily from six to eighteen months is not easy. The illness itself, medication side effects, and the near constant of underlying poverty and food insecurity make it even harder. Which explains why as few as 70% of MDR-TB patients successfully finish their treatment.

All of these jobs are essential to Mots’elisi’s care. But none are as close to home, as daily and dedicated, as that of the treatment supporter. “I never would have made it without her,” Mots’elitsi says about ‘Mme ‘Malerato, who has become like an auntie to her. “She never missed, and it made me feel like someone was on my side.”

As for ‘Mme, she has now accompanied several patients over the years. She receives payment for her work, and with a new baby at home the money coming in goes a long way. She also appreciates the chance to make a difference. “I know that when I go to see the patients, I’m able to help them understand and motivate them to take their medications.”

The accompaniment model is central to PIH’s vision of care. The organization believes in paying local health workers and in providing for more than just the immediate medical needs of the patient. PIH’s connection to community allows them to build the team that can deliver that care.

It’s not an easy time for Mots’elisi –completing MDR-TB treatment is hard work – but she’s going to be ok. Thanks to the care of people like ‘Mme ‘Malerato, community connections become personal connections. Those connections help patients like Mots’elisi feel loved and valued, and ultimately to be cared for and cured.

This work in Lesotho reminds us a lot of our TB work in Saskatchewan’s North, dealing with a problem that is neither long ago nor far away.

More snow, no mountains, but remote communities, crowded housing, a persistent problem with tuberculosis, and the need for a team-based approach, mean there’s a lot that Canada and Lesotho can learn from each other in the fight against TB. And with recent increases in TB cases in Saskatoon among people living with HIV, we’d best be ready to learn and act quickly.

And with one more World TB Day special, here’s author, vlog brother, and self-professed “TB Hater” John Green talking about the STP - Screen, Treat, Prevent - Approach to ending tuberculosis.

All photos Josh Berson except map and helicopter.

As we have all hands on deck in dealing with this curable disease, TB! Until we end TB, PIH Lesotho supporting the group government, will offer the preferential option, innovative and compassionate care for our patients.