Welcome to Part Three of this three part series on syndemics (see Part One here and Part Two here), but first a note on an upcoming Global Health conference on March 6th.

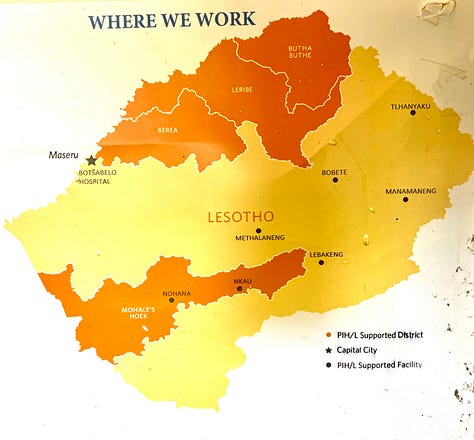

Mahli and I are honoured to be presenting on experiences with TB treatment with Partners In Health Lesotho in the upcoming conference Global Health: Lessons From Abroad from 1:30 - 5:00 CST. Tickets are free and you can join on campus in Saskatoon or online. Register at this Eventbrite page to attend.

A Hard Road

You don’t drive to Methalaneng, you bounce there. After two hours on a winding mountain switchback tarred road, you spend an hour on a winding dirt road followed by two more on a winding rock trail, arriving at the remote health centre far in the Lesotho highlands rattled and sore.1

The patients, on the other hand, haven’t had it so easy. They’ve walked hours through the mountains to reach the clinic. A twelve-year-old boy and his little sister left their village before dawn, both have been coughing for weeks. By pure coincidence, they turn up at the health centre on the same day our team of pediatrician, infectious disease specialist and two general practitioners came to visit. The kids were hungry and scared, terrified of being examined, but they stuck around long enough to be diagnosed with TB and started on medications.

These coincidences are something anyone who has worked in global health will tell you about. The chronic but curable pathology gone unaddressed for years, the patient who presents with a toothache only to leave on treatment for HIV and TB, these happy accidents of being in the right place at the right time are rewarding. You make a difference in one life and that is not something to shrug off. At the same time, they leave you wondering about every other day, all the opportune moments for care when there wasn’t someone there. Ultimately that’s what strengthening health systems is about: increasing the frequency of these occurrences until coincidence becomes consistency.

As we were packing up the pickup to get back on the road, a family appeared with two small children. Very small. The eight-year-old looked to be three, the two-year-old was the size of a six-month-old baby. Both were suffering the consequences of severe malnutrition; their family simply didn’t have enough to eat. They needed medical care and evaluation for acute and chronic illnesses, but the underlying problem wasn’t clinical, it was social.

The Great Syndemic

We’ve talked in this series about syndemics, the connection between different illnesses like TB, HIV and COVID. There are dozens more examples of diseases that combine to worsen the effects of the other at the level of the individual and the community, but there is one great syndemic, one thread that runs through it all: poverty.

Back home in Saskatchewan that poverty looks different. There is still malnutrition, but rather than not enough food, many people can only afford calorie-rich, nutrient-poor foods, a diet that carries risks of its own. Patients may not have to walk hours through the mountains, but instead find themselves flown for clinical care from the North to the city, far away from social networks and supports. Or, due to lack of transport and inaccessible hospitals and clinics, may simply not be able to afford to get across town to an appointment. Remote and rural, low- and high-income countries, underfed or badly fed, homeless or badly housed, poverty has many faces, but illness always seems to be able to pick it out of a crowd.

Imagine doctors suddenly discover a disease that they’d previously overlooked. Once they recognize it, however, it becomes clear that it is a huge problem. Over 10% of Canadians are directly affected; young and old; men, women and children. It kills more people per year than stroke, diabetes, accidents and COPD combined. Billions are lost through decreased national productivity and increased health costs. Flying below the radar of traditional understandings of illness, this disease has quietly been loading an enormous burden on the health of Canadians.

If a new disease with such disastrous effects appeared, certainly there would be a massive outcry. We would expect the government to have a plan in place immediately, mobilizing all of the resources necessary to find a cure and prevent the spread. We would demand national campaigns informing citizens of the risks and the quick establishment of treatment centres across the country.

Well this is exactly what’s happening right now in Canada. And the condition that leads to so much death and disability? Poverty.

The negative health impacts of poverty are astounding, making it the most urgent preventable health issue facing the country. People living in poverty are at a higher risk of a broad range of communicable and non-communicable diseases and injuries. The additive effect of all of these conditions is a mortality rate double that of the rest of the population. 40,000 excess deaths per year have been attributed to poverty; only heart disease and cancer kill more. People living with poverty suffer higher levels of a litany of infirmities: diabetes, COPD, heart disease, depression, HIV/AIDS, and various types of cancers. 10% of Canadians are poor, and this results in a loss of over 70 billion dollars per year to the national economy through decreased productivity and increased health and social service costs.From Chapter 5, The Search for a Cure for Poverty, A Healthy Society 2017 Edition

The quote above seems oddly prescient after our experience of the COVID pandemic, given how we did mobilize on that acute threat but continue to respond inadequately to the chronic killers. While there was much talk of being in the same boat, COVID hit poorer communities harder than wealthy, both in the direct effects of infection as well as financial challenges. We see this vicious symbiosis of poverty that sickens and sickness when people lose their jobs due to illness or have to forego the basics because they can’t keep up with medical bills. The reverse can be true as well, where financial support can turn illness around and give people the space to find opportunity. The recent RATIONS study in India saw a 39-48% reduction in tuberculosis among household contacts when the family received nutritional support.

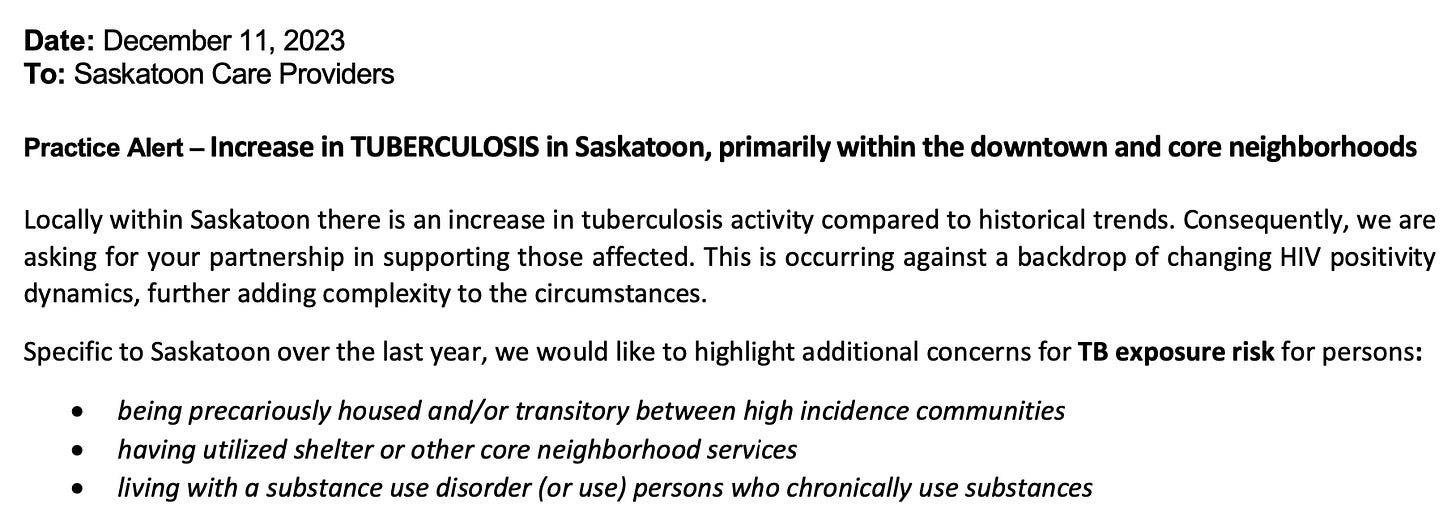

HIV is connected to poverty the world over, including in Saskatchewan where connections have been made between some of the lowest social supports in the counts and the highest rates of HIV in the country. Unsurprisingly, the province’s persistent endemic TB is now finding its way into poorer urban areas where HIV is prevalent. A spike in new cases among HIV positive patients prompted a public health practice alert late last year, specifically identifying the added risks of precarious housing and substance use disorders.

Similar patterns can be seen for diabetes, heart disease, and countless other infectious and non-infectious conditions. The evidence is clear, poverty makes people sick. If there’s to be any hope for a cure for the great syndemic, we need to first acknowledge that this is a systemic problem, not a question of individual choices or just plain bad luck. When one person’s health is poor, you can question their behaviours, genetics, fortunes etc., When whole groups are over-represented in illness, the health behaviours that need to be examined are those of governments.

"Poverty wields its destructive influence at every stage of human life, from the moment of conception to the grave. It conspires with the most deadly and painful diseases to bring a wretched existence to all those who suffer from it." WHO Bridging the Gaps report, 1995.

Murder By Numbers2

Michael Marmot talks of “social injustice killing on a grand scale,” while others, like Dennis Raphael author of the Social Determinants of Health: Canadian Perspectives, have revived the use of the term “social murder.” Partners In Health co-founder Dr. Paul Farmer wrote frequently about the concept of structural violence, where social structures prevent people from meeting their basic needs and result in unnecessary and avoidable suffering. These ideas lay out it no uncertain terms how high levels of illness are the result of persistent political choices, dangerous health behaviours on the part of decision-makers, especially those in the world’s wealthiest countries.

There is an enormous difference between seeing people as the victims of innate shortcomings and seeing them as the victims of structural violence. Dr. Paul Farmer, Pathologies of Power

This can be dark and depressing stuff; it’s hard to find a silver lining when discussing the realities of human suffering. But the truth is, the world has come incredibly far in reducing poverty. In 1975, the year I was born, 40% of the world’s population the world lived in extreme poverty as defined by the United Nations. Now, just under half a century later, that number is less than ten percent. That decrease is partially offset by population growth, meaning the gross number of people living in extreme poverty is still about half what it was in 1975. Nonetheless, it's a remarkable improvement and cause for celebration.

But it is not cause for complacency.. There are fewer people living in extreme poverty now, but their lives are as hard or harder than they were in years past. The means to help - be they technological, financial or medical - are more abundant and more powerful than they have ever been. There are those that argue that since inequality and poverty are improving we should stop any redistributive efforts, the most striking being Argentina’s new libertarian evangelist president, Javier Melei, a newfound darling of the North American right. The last ten percent of extreme poverty will take massive deliberate efforts to eradicate, it will not be some happy accident of free market liberalization. And extreme poverty is not the only measure that matters, as health impacts are felt all along the wealth gradient, with a low relative position in a society can be as damaging to health regardless of higher overall incomes.

Medications and health services are necessary, but they will only take us so far. They are the response to illness, they won’t get at its source. A focus on the upstream factors, reducing the still very real burden of poverty at home and abroad through education, aid etc. In a recent Webinar for International Development Week hosted by Partners In Health I was asked why people in Canada should care about global health.

The first, and truest answer, is that whether they’re in Methalaneng, Minneapolis or Moose Jaw, people’s lives matter. We should care because we’re human. That’s when we’re at our best. It’s also fair to say that, as COVID showed us, that we live in an increasingly connectecd world, one where ripples of disease, or natural disasters, or refugee crises continents away wash up on even the most landlocked of shores. When people in places we’ve never heard of are healthy and prosperous rather than hungry and desperate, the world we inhabit is safer and better as well.

Better health remains the best measure of our success as a society, within and across borders. There is no path to greater health that allows poverty to exist at the levels it does today.

If the causes of sickness are political, then the answers must be political. To truly improve health outcomes we must address the roots of sickness: unemployment, adverse childhood events, social isolation, homelessness, and food insecurity. In a word, if we want people to be healthy, we need to find a cure for the real disease. We need to find a cure for poverty.

From Chapter 5, A Healthy Society

Thank you for your patience with this deeper dive (and a bit more time between posts to prepare it). As always, your comments and suggestions for new topics to explore are very welcome.

All photos my own, road video Dr. Prithiv Prasad, PIH.

Deep cut from the 1983 Police album Synchronicity (not Syndemicity)

Excellent writing in bringing this all together, Ryan.

I recently listened to the chapter on the search for a cure for Poverty from your A Health Society book & it’s a timely reminder of how the ideas you put forth over a decade ago are still valuable for the work needed right now.

As always, thank you, Ryan, for your commitment to equality and a better world.