Trust Issues (Part III)

Bias, balance and a modest proposal for the Mother Corp

A Fine Balance

This is the third in a short series on issues of trust and misinformation.

In this final instalment (for now), I want to move from health experts and elected leaders to the people who tell their stories. Not only has the profitability of traditional media been undercut by social media, but its credibility as well. There’s great value in critical thought and interrogation of official and mainstream sources, but we’re now well past the point of any common understanding of the world around us. COVID briefly presented a moment of looking in the same direction, but this singular event soon passed through the prism of our scattered and views, leaving people to interpret a common experience in completely opposite ways. This fragmentation makes the work of journalists and the companies that distribute their work more important than ever, and potentially more dangerous.

We need people committed to the craft of telling the truth and telling it well.

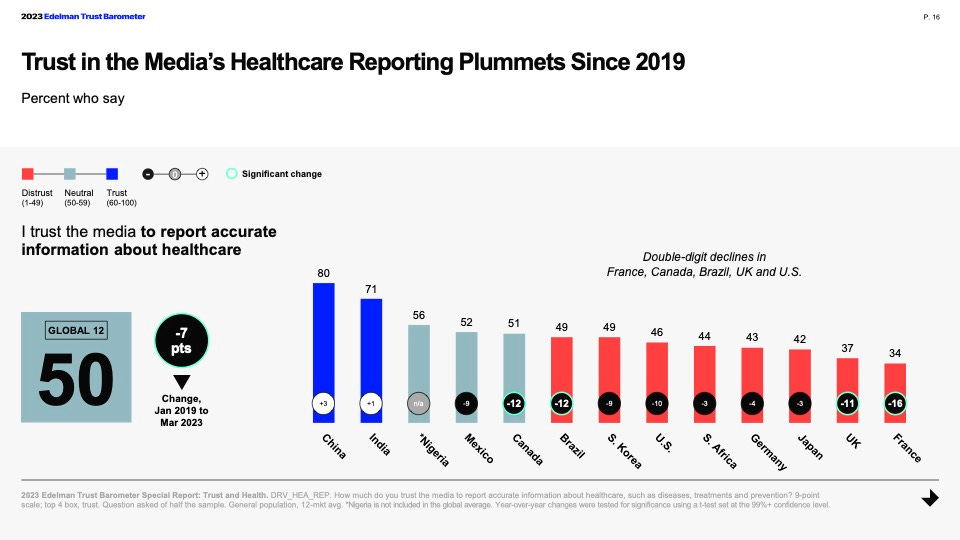

In Saskatchewan, reporters did a tremendous job of reporting the substance behind the spin during and post-COVID. For example, this April 2024 article from Alexander Quon and Zak Vescera that digs back into what Scott Moe and co. really knew as the Delta wave was set to overwhelm Saskatchewan hospitals. As much as it may be a struggle to push through the noise, what reporters choose to cover, and their newspapers, websites and broadcasters choose to publish, still matters. At a time when trust in media to tell the truth about health issues is falling around the world, we need people committed to the craft of telling the truth and telling it well.

From Both Sides Now

People in media write a lot about media, as you would expect, and for reasons the graph above explains, trust is the topic of the day. At the heart of the debate is a battle over the idea of impartiality, a two-sided argument about bothsidesism. In this year’s Massey Article, The Trust Spiral, journalist Tara Henley describes a loss of confidence in mainstream media that is preceded and precipitated by a loss of profits and players. She makes a case for objectivity and points the finger at the “wokeness” or “identitarian moralism” of young, left-leaning reporters as the source of its decay.

On the other hand, there isn’t always another hand.

There are good points in the piece, including the critique of what can be an alienating focus on group identity as a stand-in for equity. She’s right to argue for a reporting of the facts rather than infusing writing with the moral views of the observer. On the other hand, she fails to note that there isn’t always another hand.

Journalists should report the facts, including those that are ideologically inconvenient. They aren’t, however, obliged to include information that has been disproven. The world is not flat. Donald Trump didn’t win the 2020 US election. People have the right to believe the contrary, but reporters shouldn’t include their views in serious reporting, that’s false balance. This is where Henley’s argument fails her own test. She discounts things she disagrees with, such as coverage of COVID and the Freedom Convoy, with a broad brush, for example over-stating the degree to which the Public Order Emergency Commission exonerated convoy protesters. She then fails to include arguments from those who would think these things were covered well or to include concerns of journalistic malpractice from right-leaning outlets such as Fox News where misinformation has been flourishing.

A similar story unfolded in the US, where longtime NPR contributor Uri Berliner said that his (now former) workplace was losing the trust of Americans because of a lack of viewpoint diversity. His NPR colleague Steve Inskeep reviewed the piece, pointed out numerous errors and the lack of any dissenting views, pointing out that, “Berliner gave a perfect example of the kind of journalism he says he’s against.” This is where we need to be cautious, when actors like Matt Taibbi or Bari Weiss call for the inclusion of more viewpoints, are they calling for broader objectivity, or for more media to reflect their own opinions and exclude others? A return to fact-based reporting has to find a path that avoids the delegitimizing practice of false balance and that interrogates bias from all directions.

A Modest Proposal for the Mother Corp

Good quality news is an essential public service. What if, instead of defunding our public broadcaster, we improved it and widened its reach with a CBC newspaper?

Some people will hate this idea, of course, as support for the CBC has become a defining political line. Its continued existence under a potential Poilievre government is very much in question, and the country would be poorer as a result.

In Canada, we have a failing or failed newspaper industry. Many regional papers are now the “ghost papers” Henley describes in her article, reprinting national coverage and advertorial content with very little local information. This leads to what former Boston Globe editor calls a “corruption tax,” where communities like my hometown of Moose Jaw, that lost the Times Herald after over 125 years, or the Whitehorse Star that closed last month after a similar tenure, lose the watchdog function that can keep local officials honest.

A national CBC newspaper, publishing on paper the stories that are already being produced for radio, TV and online, could make sure that good local reporting happens while giving readers across Canada a shared experience of the news. It could also help revitalize the information deserts where local papers have disappeared or are so empty that no one would notice the difference.

Now to the objections:

1) It would cost too much. This is a blue-sky exercise, I won’t pretend to have done the math, but it surely couldn’t cost more than the $600 million public dollars to private corporations that still shed jobs and close bureaus. Public bailouts of private media have worsened trust in media without achieving the intended preservation of quality coverage.

2) It would drive existing papers out of business. To some degree that’s a moot point; they’re already going or gone. It’s also worth pointing out that TV, radio and online news have not been harmed by the existence of the CBC. If anything, it contributes to competition that enhances the media landscape.

3) It would tip the scales. Isn’t this article about bias and trust? Wouldn’t this just be more Liberal propaganda? Here’s where work would need to be done. The CBC’s reputation for bias is far worse than the reality. But it isn’t just perception. Independent media bias reports do score the corp as highly factual but with a left-centre bias.

My experience is that a more liberal worldview tends to show up more in stories on public stories rather than coverage of partisan politics, for example in reporting on LGBT issues or First Nations concerns. As a left-of-centre politician, my interviews with CBC reporters were frequently more combative, with some reporters telling me they needed to be tougher on the NDP than the Sask Party to overcome the perception of bias. For this newspaper idea to succeed, or for the existing programming to stop being a political football, the CBC needs to strive for greater objectivity and impartiality.

Before we get too carried away about bias at the CBC, however, let’s remember what we’re talking about with every other outlet. While reporters may skew left, newspaper owners certainly don’t The CBC has never endorsed a candidate or a party, whereas PostMedia will endorse the Conservatives no matter what they do. The editorial pages of most of Canada’s newspapers make no bones about where their sympathies lie and they aren’t on the left. Private companies and have the right to promote their own opinions, that’s their business, though it does ger stranger when public dollars are flowing their way. Nonetheless, as a public news agency, the CBC should be held to a higher standard and take further measures to be and appear impartial.

A factual, objective and well-written CBC broadsheet in the mailboxes of Canadians could reverse the erosion of our information landscape. It could be a source of unity rather than division, helping to build back trust in the news and each other.

Thank you for reading (and trusting) A Larger Scale. This post is public, feel free to share it.

Just a few points about your proposal. Simply stated, there is no such animal as 'fact based reporting', as facts don't exist outside an historical context, and that context is itself a battle ground of ideological contestation.

An example to ampllify this. 'The war in Ukraine began on 24 February, 2022'. Did it? Or did it begin in 2 May 2014 when the Right Sector neonazis burned 46 people alive in the trade union house in Odessa, thereby percipitating the organization of the Donbas militias which defeated the disinitgrating Ukrainian army in the Luhansk region. A defeat which lead to the intervention of the German and French political leaders agreeing to the Minsk Accords.

Or did it begin with the Maidan coup where the USA deputy undersecretary of state Victoria Nuland picked who was to become the next leader of Ukraine? Or did it begin in 2008 when George Bush stated that Ukraine would become a member of NATO, despite the objections of France, Germany and most importantly Russia, who warned Washington that this was a red line that could not be crossed. Or was it in 1991 when NATO invited Ukraine to join the North Atlantic Cooperation Council, and Russia put forward the idea of it too becoming part of an overall European Security architectture?

One could reasonably argue that each of the events mentioned above was the fact which was that one thing which started the war in Ukraine.

Similarily, the notion of impartiality in reporting is just as illusional. What storiers to cover, how they are chosen, who chooses them, indeed what constitutes 'news' is itself open to interpretation and is conditioned and structured by one's vierwpoint on the world.

So far from trying to resurrect a dead parrot, the idea of an impartial public broadcaster, isn't it much more important to champion the freedom of the electronic media and to organize against its censorship, like the USA trying to outlaw TikTok, or Canada's ban against RT and Sputnik, or Ukraine's move to outlaw Telegram, or the repression against real journalists like Julien Assange or Eric Snowden, and the mass murder by the Israelis of journalists in Gaza?

In health, I am grateful to those who tell the truth & tell it well.